Betting on Green Hydrogen in Chile, a Road Fraught with Obstacles

15 Juni 2021

15 Juni 2021

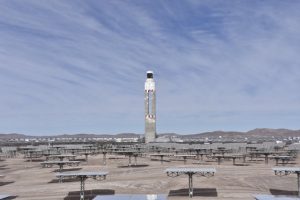

The Cerro Corredor solar complex in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile became the largest photovoltaic plant in operation in Latin America when it was inaugurated on Jun. 8. CREDIT: Cerro Corredor

By Orlando Milesi

SANTIAGO, Jun 15 2021 (IPS)

Chile is in a privileged position in the world to produce green hydrogen and boost the development of the new fuel thanks to the country’s optimal conditions for generating solar and wind energy, but the large investment required and the scarcity of water are two of the biggest obstacles to overcome.

This South American nation’s National Green Hydrogen Strategy aims for Chile to produce the world’s cheapest green hydrogen by 2030, to become a major exporter by 2040 and to reach an electrolysis capacity of five gigawatts (GW) by 2025.

“Our main goal is to become one of the top three exporters of green hydrogen worldwide by 2030, producing approximately 2.5 billion dollars worth each year at the lowest global cost,” said Minister of Energy and Mining Juan Carlos Jobet.

“We are extraordinarily blessed with some of the best solar and wind resources in the world,” he said on Jun. 2, alluding to the heavy solar radiation in the northern Atacama Desert and the strong winds in Patagonia, in the southern Magallanes region.

Chile increased the goal for clean electricity generation to 40 percent by 2030, coinciding with the Jun. 8 inauguration in the northern region of Antofagasta of the Cerro Dominador Complex, which became the largest solar plant in Latin America. A goal in which green hydrogen is beginning to enter the equation.

According to Jobet’s calculations, by 2030 Chile will produce hydrogen at 1.50 dollars per kilo, a price competitive with fossil fuels. The minister forecasts a potential market of 25 billion dollars that same year.

Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, was already used for refining oil, methanol or steel, for example, but was generated from fossil sources, thus contributing to the emission of polluting gases.

Green or renewable hydrogen, on the other hand, is a fuel obtained by electrolysis of water, a process that separates hydrogen from the oxygen contained in water, using electricity from clean sources, such as solar and wind power, so as not to contribute to global warming.

Energy represents 70 percent of the cost of this process, so it is crucial to boost the steady decline of prices of these sources in the country.

Marcelo Mena, a professor at the Catholic University of Valparaíso, former environment minister and member of the government’s Green Hydrogen Advisory Committee, told IPS that the Strategy “is possible, but it requires a change in the way industrial policy is made in Chile.”

“Unlike in history, where ideologies have led governments to say that the market has to choose the winners and not States, I believe that here we have to choose, stake our bets on and seek comparative advantages. Betting on what Chile is in terms of its production,” he said.

Mena argued that “a high level of financing is required in the transition” and gave as an example the subsidies in Germany, equivalent to some 700 million dollars a year, while “what we have put in so far is 50 million.”

“A more robust subsidy is needed, a greater amount of funds because they are emerging technologies that require reducing the risk for investors,” he said.

By way of example, Mena said “a large green hydrogen project, from one to two gigawatts, requires an investment of close to one billion dollars.”

According to Mena, a leading expert in energy transition, green taxes can provide part of these resources.

A mock-up of the Haru Oni plant, which is about to begin construction in the southern Chilean region of Magallanes, where it will take advantage of the abundant wind energy provided by the area’s strong winds. With an investment of 45 million dollars, it will produce ecological methanol based on green hydrogen and the resulting gasoline will be used in conventional vehicles. CREDIT: Siemens Energía

No lack of doubts

Consultant María Isabel González, manager of the company Energética and former executive secretary of the state-owned National Energy Commission, has doubts about the country’s bet on the so-called fuel of the future.

“Producing green hydrogen in Chile is an overly ambitious goal, which is not in line with the circumstances here. Just compare the investments being made in countries like Australia, with projects for more than 27 gigawatts and an investment of 36 billion dollars,” she remarked to IPS.”What is needed is a strategic look at what is going to be done with water, waste, citizen participation, transmission, space demands. Everything has to be transparent and discussed with the community. Otherwise, those who could be our promoters may become detractors.” — Marcelo Mena

She also argued that the idea of green hydrogen stood in marked contrast to the energy poverty suffered by half of the population in this country of 17.5 million people, who still have no access to hot water, while thousands of households use firewood for heating.

“Obviously a developing country like Chile should first solve the basic needs of its population and in particular of those most in need,” González argued.

That is why she suggests delaying green hydrogen plans.

Mena agrees that energy poverty is a problem, but believes that the situation can be addressed simultaneously with the production of hydrogen.

“We can promote an industry that generates revenues of around 20 or 30 billion dollars a year and with these higher revenues we can electrify the energy mix by replacing polluting firewood, which is expensive and causes high levels of deforestation,” he said.

Another issue is that generating green hydrogen requires a lot of water. According to González, nine tons to produce one ton of hydrogen. But Chile is facing a major drought that has lasted for more than a decade.

She said “this could be solved with seawater desalination,” but added that “this is not our only disadvantage” and cited the “significant” problem of Chile’s distance from the main markets.

This long and narrow country nestled between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Ocean can export its products through its Pacific coast ports, ship them up through the Panama Canal or transport them across several South American countries to reach the Atlantic.

Mena believes that “the amount of water required is much less and there are ways to find this water without causing conflict. One is desalination and another is the use of sewage that today is discharged raw into the sea in northern cities.”

The Canela Wind Farm, with wind turbines 112 meters high and an installed capacity of 18.15 megawatts, generates electricity with wind from offshore in the Coquimbo region of northern Chile. CREDIT: Orlando Milesi/IPS

Darío Morales, director of studies for the Chilean Renewable Energy Association (Acera), which represents companies and professionals in the sector, admitted to IPS that water is a challenge that should not be minimised.

But he also mentioned the desalination option and pointed out that “one of the objectives of developing the domestic hydrogen market is to use it to replace fossil fuels, the refining of which also uses significant amounts of water.”

The investment challenge

Morales also noted that the Strategy calls for five billion dollars to be invested in hydrogen development by 2025, “which is an enormous challenge, especially if we consider that this must be accompanied by a major boost for renewable energies.”

He said these clean energies should at least double their current generation capacity.

According to Minister Jobet, Chile has the capacity to generate 70 times more renewable electricity than what it produces today.

Mena said the Strategy includes “investments of over 300 Giga of solar energy. In terms of panels per person, this would be 15 KW of power, equivalent to 40 solar panels for each Chilean.”

He said it was important to submit the plans to a strategic environmental assessment that would allow for consultation on this policy and look at environmental aspects.

“What is needed is a strategic look at what is going to be done with water, waste, citizen participation, transmission, space requirements. Everything has to be transparent and discussed with the community. Otherwise, those who could be our promoters may become detractors,” he said.

He also warned that “today green hydrogen is not competitive.”

“Costs have to come down, like they did with solar energy, whose costs were reduced by 90 percent in a couple of decades,” Mena said.

González noted that “according to the International Energy Agency, one kilo of green hydrogen, which contains about 33.3 kWh, costs between 3.50 and 5.0 euros (each euro is equivalent to 1.22 dollars), which means between 100 euros/MWh and 150 euros/MWh.”

A glimpse of dawn amidst the steam from the geysers of El Tatio, in northern Chile. Geothermal energy is another clean, non-conventional energy, in this case also infinite, which Chile is beginning to harness with the Cerro Pabellón Geothermal Power Plant in the municipality of Ollagüe. CREDIT: Marianela Jarroud/IPS

“To be competitive it should reach around 60 euros/MWh, or around two euros per kilo,” she said.

The Strategy aims for a cost of 1.30 dollars/kg H2 by 2030 and 0.80 cents/kg H2 by 2050. One cost reduction would come from lower electricity prices. Another would come from economies of scale, for which it is essential to develop domestic demand.

To reach this goal, “policies for the development of specialised suppliers and local technological development should be promoted. If any of these pillars fail, it will be difficult to achieve the expected cost reductions,” said Mena.

Eduardo Bitran, designated as one of 20 ambassadors of green hydrogen by the government of Sebastián Piñera, said the domestic market is led by the mining industry. “Moving towards green mining is a starting point,” he said. This would be followed by use in long-distance heavy-duty transport and passenger transport.

He said the coronavirus pandemic “has made us realise the extent of global interdependence.”

“The great post-pandemic threat is climate change. This is the last decade to prevent the planet’s temperature from rising more than two degrees Celsius,” he said at a meeting of the Innovation Club, which he chairs.

Countries with productive potential and other consumers agreed to join forces to turn hydrogen into an alternative to fossil fuels, during an international meeting organised in Santiago in preparation for the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) on climate change, to be held in Glasgow, Scotland in November.

Australia, Chile, the United Kingdom and the European Union will seek to make green hydrogen affordable and competitive, they agreed at a virtual meeting on Jun. 3.

Minister Jobet stated that “what we have to do as a planet to use this hydrogen at an accelerated rate is to reduce its cost, because it is still more expensive to produce, transport and store than its oil or gas alternatives.”