Climate-driven salt water threatens New Orleans and beyond

30 September 2023

30 September 2023

People in New Orleans are preparing for the impacts of salt water intrusion caused by the 2023 summer drought in the United States, though sea level rise and other climate impacts also are raising the salt-water risk for agricultural loss and drinking water access around the world.

With New Orleans, it’s important to remember that the city sits below sea level along the heavily trafficked Mississippi River, near where the major U.S. waterway empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Fresh water normally flows down the river and into the gulf, but hot and dry conditions have meant two years of low water levels, some of them record-setting. This has affected key shipping routes but, in recent weeks, began to impact drinking water.

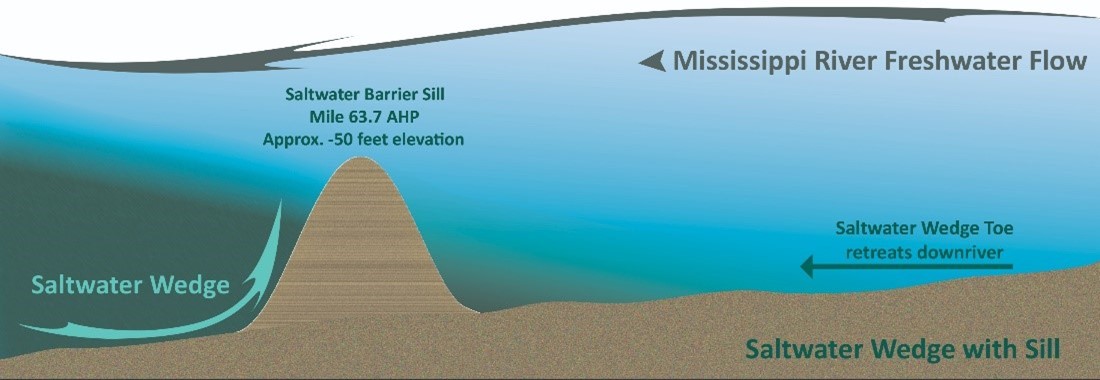

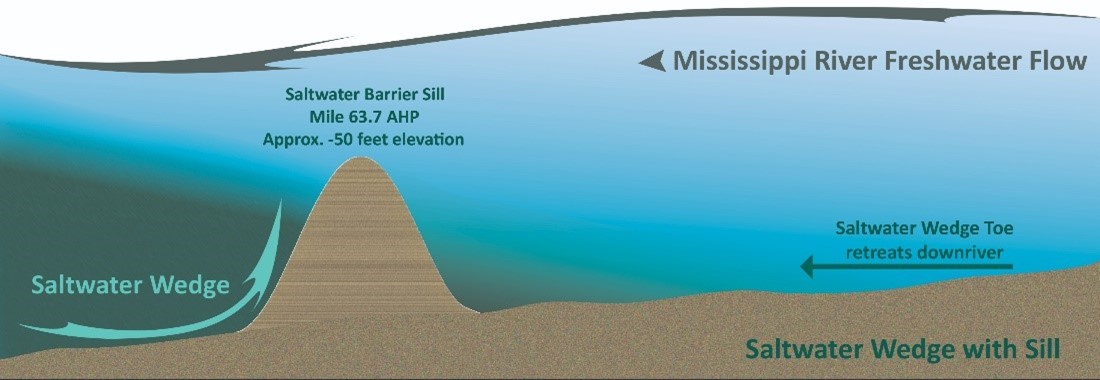

That’s because salt water is creeping up from the Mississippi Delta just below New Orleans, a city of more than 350,000 people. The salt water is more dense than fresh water, so it tends to move along the river bottom while forming a wedge with a “toe,” the point of the wedge that arrives first. When it does, that means that salt water that’s reaching the surface is about 15 miles behind it and moving upriver.

Plaquemines Parish, at the edge of the gulf, already is affected by salt water intrusion, with city officials warning that St. Bernard, Jefferson and Orleans parishes are forecast to experience the impacts within the next few weeks. The Algiers neighborhood, where there’s a water intake for an estimated 9.9 million gallons per day (MGD), will see salt water effects on October 22. For Orleans Eastbank, with 141 MGD, it’ll begin October 28.

“New Orleans and the other regional parishes get our municipal water supply from the river, so if the salt water reaches our water intakes it will threaten our ability to provide drinkable water,” the city says.

There’s little that can be done. Engineers have raised the sill (a sort of underwater dam that blocks salt water back flow) and say it will slow the advance, but they can’t stop it.

“The only other thing that would stop the wedge is an increase to the river’s flow. Unfortunately, drought conditions are expected to persist up north and no relief is in sight,” the experts explain. “Long-term forecasts can always change, but we have been told that the low river situation could persist until January or later.”

Solutions include diluting salt water with tanker water, but it’s unrealistic that imported water can meet demand. Connecting to a nearby system has structural compatibility challenges, and there’s not enough time for desalination at scale. Reverse osmosis machinery can help to filter the water; it was delivered to Plaquemines Parish on Thursday, where people have been limited to bottled water.

The impacts go beyond drinking water safety and the problem of salt water intrusion reaches far beyond New Orleans. Corrosion and infrastructure damage occur with salt water exposure, and damage to agriculture and ecosystems is unavoidable. In the U.S., salt water intrusion is a challenge along the East Coast. In Asia, it’s a problem for Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India, among others, and especially along the Mekong Delta.

In North Africa, where water resources are threatened for a host of reasons, salt water intrusion threatens aquifers in Morocco, Egypt, and other states where 60% of the populations live in coastal zones.

Long-term climate adaptation strategies from U.S. officials include improved groundwater monitoring, water access and storage infrastructure, as well as water conservation and changes in land use. In the meantime, President Joe Biden has declared a federal emergency for the incident and New Orleans is preparing for impact.

The post Climate-driven salt water threatens New Orleans and beyond appeared first on Sustainability Times.