From Pine Ridge to Palestine: Indigenous Solidarity in the Ceasefire Movement – an Interview with Nick Tilsen

14 Februari 2024agnes

By Cristina Verán

As of this writing, more than 27,000 people have been killed by Israel’s war on Gaza—the overwhelming majority of whom have been Palestinians. Evidenced by the sheer scale of destruction, the Israel Defense Forces’ response to Hamas’s horrific massacre of Israeli citizens on October 7, 2023, is now widely viewed as a use of disproportionate force. The death toll continues to rise, and the incessant bombardment of this wedge of Mediterranean coastline not only levels buildings and annihilates communities, it heralds an era of environmental devastation with no end in sight that will impact generations to come.

Popular opinion worldwide continues to coalesce around demands for an immediate ceasefire, and Indigenous voices have become especially prominent in support of Palestine in a spirit of kinship for its people. At the same time, calls for the dismantling of Israeli settler-colonialism, framing the country’s military actions as genocide, have been met with swift retorts from pro-Israel voices in media, politics, and academia. Many imply that Indigenous Peoples’ (and other Palestinian-aligned) perceptions and critiques against Israel are somehow unjustified, ahistorical, and even inherently antisemitic—a framing that reads as disingenuous, however, when scores of Jews in the U.S. also resist and have joined in the protest movement.

A troubling pretense has emerged in the public debate with regard to exercising what, in the United States, is a constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of speech. Though citizens of the U.S., including those of Indigenous Nations within it, may ostensibly criticize the U.S. government with impunity, those who speak out against the State of Israel face censure, sometimes losing their jobs, for doing so. All the while outspoken antisemites from the far-right face scant interrogation over their staunch support for the Israeli government—even as their own interests may be otherwise dangerously at odds with the wellbeing of Jewish people.

Cristina Verán recently spoke with Nick Tilsen, President and CEO of the Indigenous-led advocacy and grantmaking organization NDN Collective, about his personal story—being both Oglala Lakota and Jewish—as well as organizational philosophy of support for the Palestinian people in this brutal conflict. His speech at Freedom Park, a high point of the Free Palestine/ Ceasefire March in Washington, D.C. last fall, made special note of his dual heritage, emphasizing the impact that his Jewish activist grandfather has had on his viewing this war through an Indigenous lens.

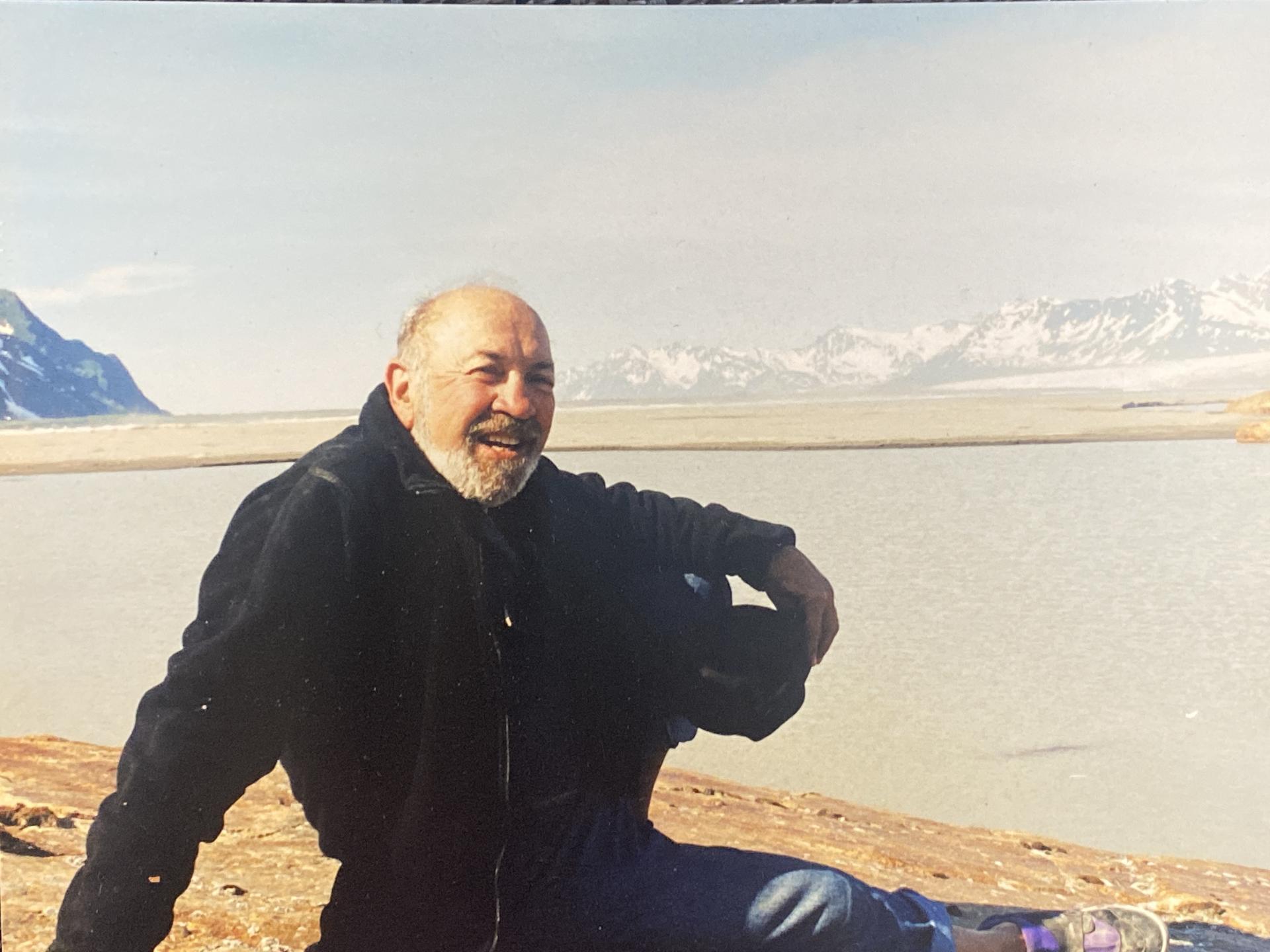

Nick Tilsen with his grandfather. Photo courtesy of Nick Tilsen.

Cristina Verán: You come from a family with a notable activist pedigree on both sides, deeply engaged in actions for justice. Tell us a bit about this foundation and how it grounds you.

Nick Tilsen: First of all, I hold two different identities: I am Lakota and I am Jewish. I was born on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, where I grew up going to Sundances. But I celebrate Passover, too. My mom’s Lakota side of the family is Oglala, from Pine Ridge. My father’s side is all Russian Jews (our original last name was Teplinsky) from the border area of Russia with Poland. They came to the U.S. as part of the wave of Jewish people arriving at the turn of the century, not through Ellis Island but Canada, crossing over by Niagara Falls.

My mother, JoAnn Tall, was a young organizer and activist as a student in the 1970s. She was part of the Oglala Civil Rights Organization, which first invited the American Indian Movement to come to Pine Ridge because of corruption in the Tribal government at the time. I was raised within that movement, but my Jewish side was also very active.

Nick Tilsen grandfather’ Ken Tilsen. Photo courtesy of Nick Tilsen.

My grandpa, Ken Tilsen, was a great influence on me. He was a Civil Rights attorney and one of the original lawyers for the American Indian Movement when it was first getting started on the streets of Minneapolis. He supported AIM when they explored pressing charges against the Minneapolis Police Department back in 1968. Then in 1973, when the Occupation at Wounded Knee happened, they needed lawyers, so my grandpa came out to help. My father [Mark Tilsen, Sr.] came with him, and my parents actually met each other there during the siege.

CV: From early on then, the Jewish side of your family forged deep connections as allies with Native Americans in their struggles. When did you begin to realize the significance in how, for them, Jewish history and identity are clearly linked to notions of justice?

NT: Lakota culture is strict, like, ‘Shh! Be quiet! Watch and you’ll learn! Behave!’ But in Jewish culture, there are times when young people can openly question the Elders. So, imagine when I’m like nine years old, this Jewish-Lakota kid sitting there with my grandpa Ken, as he’s telling the story of Passover. Now, I already know what it means to be Lakota—our ceremonies, our language, our land—because, there on Pine Ridge, I live it. But I say, ‘I don’t know what it is to be Jewish, Grandpa. What does it mean?’ And he leans in toward me and says, ‘Well, I’ll tell you this: At different points throughout history, the Jewish people have been persecuted. And yet we have also survived persecution. That’s why we, as Jews, have a responsibility to be in solidarity with those who are experiencing persecution today. And the act of doing so… that is Jewish.’

My grandfather instilled that in me, that the notion of social justice is embedded through the very identity of being Jewish. From that moment, I thought to myself, ‘I can hold onto that.’

CV: That’s a lot for a child to comprehend, no?

NT: Back then—we’re talking early-mid ‘80s—I wasn’t into video games or those typical kid things. I loved being around all the Elders, sitting around them and just listening to them. There were always a lot of political conversations around our kitchen table; about genocide, about the theft of land, about settler-colonialism, about imperialism… so that’s the language I was around from a young age. I can remember them also talking about what was happening in Palestine, to the Palestinian people, and in the very same way they would talk about our People and the Massacre at Wounded Knee.

CV: Zionism as a political ideology is often framed by its promoters to be a kind of land rights movement. How does your understanding of it differ from that?

NT: My Grandpa Ken always believed—and I also believe—that Zionism was, and will always be, at odds with justice, so that has long been part of my political orientation.

I am not against Jewish People having their own land, at all. What I am against is [Israel as] a settler-colonial government that, by design, violates other people’s human rights and becomes an avenue for imperialism. For Jews out there who see Zionism as some kind of Indigenous rights movement, I say, “You are misguided.” That movement is leading to fascism, to the very things that are against Indigenous values about the interdependency that we all have as Peoples. In the Lakota language, we say ‘Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ’—we are all related.

CV: The indictment of Israel as a settler-colonialist state is being deflected sharply in many media outlets, from government officials, by university administrations, and others here in the U.S., with those who use the term—often linking it to genocide—frequently accused of antisemitism. How do you respond to that claim?

NT: They do not get to tell me, an Indigenous person, who is also a Jewish person, that my use of that term is antisemitic. I see these articles, these op-eds by some of the top intellectuals in the country, dismissing the charges of settler-colonialism and calls for decolonization in Palestine, while trying to tell us, ‘You just don’t understand history.’ And I’m like, ‘Are you f—ing serious?’ You know what I call that? Settler-colonial gaslighting. It’s like narrative warfare. And narrative wars help fuel the violence in real wars.

As Indigenous Peoples in the United States, we’re used to that, of course. I live three and a half miles from where the Wounded Knee Massacre happened. The sign down the road for the historic site used to describe it as just a ‘battle,’ but now, finally, there’s a plaque over it that accurately describes what took place—the U.S. Army 7th Cavalry Regiment murdered hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children (and received 19 Congressional Medals of Honor for doing so)—as a massacre.

The United States government would have us believe that the current generation does not have the appetite to digest the true history of this country, and therefore lacks the aptitude for any political analysis of the moment that we’re in. Quite frankly, if there’s going to be a future for the U.S., or Israel, for that matter, they’re going to have to change that mindset and acknowledge how what was created here is perpetuating destruction to this day.

CV: There are a number of parallels in the narratives perpetuated by both the United States and the State of Israel used to justify and legitimize the historic seizure of and dominion over lands that had already been home to other peoples. For example, the idea that pre-1948 Palestine was little more than a barren wasteland whose inhabitants “didn’t know how to use” or “did nothing” with it. Whereas Israel, having transformed that desert in terms of development benchmarks (supported by the equivalent of $300 Billion in U.S. aid alone, since 1946) positions itself as, therefore “more deserving” of the territory. That sounds familiar.

NT: Indeed. The idea that Palestine was just a terrible place in the desert with nothing until others came and ‘civilized’ it is a false narrative; a familiar one, too. That’s exactly what the United States said about our lands, depicting them as either unoccupied landscapes or as ‘rolling, desolate plains that the Natives did nothing with;’ a narrative of all-out erasure. That there were already thriving, intellectually sophisticated Indigenous societies here that had well-functioning trade economies, a functioning food system, and governments that often functioned better than the ones [the settlers] had… didn’t matter. They just thought, ‘Well, if they’re not extracting from the land, then what are they doing with it?’

CV: As Executive Director, your leadership has officially aligned NDN Collective in solidarity with the people of Palestine, and you have been vocal among those demanding an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. Describe, if you will, the foundation for this comradeship, and how it factors into the organization’s actions, activities, and platforms.

NT: There’s actually a long, shared history between the Palestinian struggle and our People going back to the American Indian Movement; a shared movement DNA that’s older than you and me. In our mutual experience of settler-colonial violence, the incarceration of our Peoples, efforts to distort and destroy our fights for liberation, and even the fact of surviving through all of that… we find comrades, brothers and sisters, relationships.

When NDN Collective set up camp at Standing Rock back in 2016, Palestinian comrades came out to support us. In those moments and in our movements, we see this, and we say, ‘You came to support us, so you let us know when you need support. We got your back.’

CV: How has this support moved beyond symbolic displays of solidarity?

NT: NDN Collective has been building relationships with the Palestinian youth movement, working with Palestinian organizers, who, in turn, have helped us to sharpen our own political spears. We’ve stood with the Adalah Justice Project, a Palestinian-led advocacy organization, doing resource-sharing, and, when we’re invited, we show up for them. In the coming months, we’ll be having Palestinian guests on our podcast, “Landback for the People,” which I host here from our Rapid City, South Dakota headquarters. Before and after this, we’ll host some organizational strategy and relationship-building exercises to share and exchange knowledge with our guests.

Nick Tilsen speaking at the November 4, 2023 Free Palestine/ Ceasefire rally and march on Washington, D.C.. Photo courtesy of NDN Collective.

CV: During the November 4, 2023 rally and march on Washington, D.C. to demand an immediate ceasefire in Gaza, NDN Collective proudly waved #LandBack banners in the midst of a sea of Palestinian flags. How is “LandBack”—as a rallying cry, a demand for reparations, and a call for restorative justice—relatable to Palestinians, as it is for Native Americans, from your viewpoint?

NT: They see Indigenous Peoples demanding #Landback, and they’re like, ‘Hell yeah!’ They want their land back, too.

CV: Have you received direct criticism from pro-Israel voices about your stance, especially because you yourself are Jewish?

NT: Absolutely. I have Jewish people saying things to me like, ‘I can’t believe you’re letting Palestinians hijack your narrative in the #LandBack movement.’ To which I reply, ‘Blood, they’re not hijacking anything. Our collaboration is very intentional.’ I make it really clear that we are fighting for collective liberation, and that, furthermore, I find their use of the word ‘hijacking’ to be white supremacist and settler-colonial AF.

CV: Does your own community, or do other Indigenous leaders and organizations, typically share your perspective, or do some need convincing? If the latter, what approach do you take?

NT: Sometimes when I talk to Indigenous leaders here, they’ll be like, ‘Gaza, that’s happening all the way over there in the Middle East. Why should I say anything?’ I reassure them that our priority is and will always be here, fighting for the return of Indigenous lands to the Indigenous Peoples of the United States. But that said, it’s important to see how the U.S. has been directly funding the Israeli military—in the billions, for decades—as it commits genocide on the Palestinian people with resources extracted from our stolen lands. How much uranium, and how much of the other materials used to make bombs and tanks being used in their attacks, comes from the oppression of our people? And so, I say we have to answer to our ancestors and act on our values. Do we stand quietly as these people are being murdered? Or, do we step into our courage and bravery, aligned with our values, even when it’s not popular to do so?

CV: The shared expectation of settler-colonial states is that the peoples whose lands they’ve colonized should eventually just accept their fates. What do you say to that, for your People and the people of Palestine?

NT: The Oceti Sakowin (People of the Great Plains of North America) are still here, and we will continue to fight for the Black Hills. The colonizer tried to beat the language out of us, they tried to beat our culture out of us, they tried to beat our connection to the land out of us—and they failed. And so, colonization… it’s not a done deal. Just like the fate of Palestine is not a done deal. Anything is possible.

–Cristina Verán is an international Indigenous Peoples-focused specialist researcher, advocacy strategist, curator, mediamaker, and educator, and was a founding member of the United Nations Indigenous Media Network and Indigenous Language Caucus. Her work brings particular focus to global intersections of politics, arts, and culture. She is originally from Peru.

Read NDN Collective’s statement: THE RIGHT OF RETURN IS LANDBACK.