What Are Our Indigenous Youth Fellows Up To?

29 April 2024Diana

.jpeg?itok=i6awkc8u)

Indigenous youth worldwide embody resilience and hope, boldly navigating systemic challenges to champion collective action within their communities. Despite facing these complexities, their unwavering commitment to growth, empowerment, and aspiration shines through. Our Indigenous Youth Fellowship Program provides a supportive platform for these young leaders to amplify their voices and advocate for change. They safeguard their lands, cultures, and languages while fostering thriving Indigenous communities. As we share their inspiring stories, let us join in celebrating their journey, resilience, and vision for a brighter tomorrow. They are the architects of transformation and the guardians of tradition, paving the way toward a more inclusive and equitable future for all.

Milpa Colectiva project from Mexico

The Milpa Colectiva was created by the community of Jose Maria Morelos in Quintana Roo to strengthen traditional farming knowledge. They continue their work this year thanks to collective efforts among the youth, grandparents, and Elders for the cultivation of Indigenous corn.

Yaritzy Soledad Naal Canul (Maya), 22, is a young farmer and student in agroecology from the Maya community. She practices Milpa, a traditional agricultural system in which maize is planted with other species, such as beans, squash, and potatoes. Milpa is a Spanish word that refers to the cornfield. She shares her experience and agroecology knowledge with the collective, hosting workshops on agroecological preparation methods that emphasize the use of safe, non-toxic products and optimizing natural components in the environment and community. On April 16, 2023, the collective held an assembly that led to agreements for the Milpa Colectiva process in 2023. The community’s oldest farmers held workshops about different types of plowing as they shared their wisdom on various forms of tillage. These workshops were intended for young participants in the intergenerational Milpa collective activities.

.jpeg)

Several visits were made to the collective’s fields to weed and prepare the land before, during, and after planting. Members of the Milpa Colectiva KM50 burned fields managed by the collective on two occasions. The youth learned from the Elders and shared traditional knowledge about burning cornfields. Support from Cultural Survival was crucial, as it covered transportation costs and the purchase of tools.

The collective organized workshops on agroecological preparation to combat pests and diseases. These practices keep agriculture free from synthetic products. As these activities couldn’t be organized within the organization headquarters, they were carried out by the farmers’ families. The project had a diversity of crops that could be planted. After discussion, it was decided to plant two varieties of Indigenous corn to avoid contamination risks and to obtain more varieties to share among community members. Unfortunately, the lack of rain and time to tend to the corn, along with wild animals damaging the cornfield before harvest, prevented the collection of corn seeds from the field.

Milpa Colectiva KM50 and partners from Ka’Kuxtal Much Meyaj visited Milpa sites and shared knowledge. Families, children, and youth enjoyed food and drinks made from corn. However, not all participants could attend this intergenerational Milpa Colectiva meeting due to heavy rain. “This year, the Milpa process was very instructive for each of us. Although we didn’t manage to increase the quantity of our seeds, we remain determined to continue promoting these practices and draw lessons from this experience for our next plantings,” Yaritzy said.

Nantu Mantilla, Ecuador

Nantu Mantilla (Pasto) was born in Tulcán, an Ecuadorian territory bordering Colombia, in an agricultural and artisan family. She studied filmmaking at the Universidad de las Artes de Guayaquil and graduated with a master’s degree in communications from the Universidad Simón Bolívar Andean University of Quito. She is the director and producer of several documentaries that were screened at national and international festivals. She previously worked as a cultural manager in her community in El Consuelo, where her family has a permaculture community center called Kimbi. For the past three years, she has been part of the Los Frailejones Ecological Club, which she has supported in the areas of communication and environmental education with a focus on the arts.

Nantu and her team of women and youth of the Club Ecológico Los Frailejones wanted to contribute to environmental education in the Indigenous pastoral farming community of La Speranza through the Laboratorio Biosocial de Botánica project. Through a long process of social struggle, the community has regained collective property rights over the El Ángel ecological reserve to ensure the protection and care of its biodiversity. This initiative was supported by Cultural Survival through its Indigenous Youth Fellowship grant. It aimed to defend the biotic, spiritual, and artisanal life of the orchards, forests, and moorland of the Reserva Ecológica El Ángel territory. This was done through the creation of audiovisual materials and the sharing of botanical care practices between people of different ages and genders. The community worked collectively to promote environmental and artistic education from a gender perspective, designed for the municipality of La Esperanza.

The project included various activities, such as knowledge-sharing meetings with children, youth, and adults on the care of nature. Several families from the Speranza community took part in a space for dialogue on the vegetable garden’s plants so they could get to know them better. The whole community was invited to the opening of the botanical laboratory, and 20 people participated. At this gathering, they participated in an important ritual for the cosmovision of the world around an altar of sacred fire seeds, flowers, and fruits. Each participant thanked a plant that had accompanied them, and some accompanied their prayers with a narration.

“My mother had a remedy made from different plants. When she gave us something, she’d say, ‘Take this.’ We drank it; it was like a drink. When I grew up, I asked my mom to teach me how to make the remedy, and she asked me for lots of things: black and white milk leaves, tobacco leaves, rue, lizard seeds, ishpingo seeds. We cooked them all. Now, when something hurts my daughters, I usually pour this remedy on them first, and if it doesn’t work, then modern medicine does,” says Teresa Paspuel, a participant in the project. Discussions on agroecology and seed and soil recovery led to the establishment of a seed altar and the sharing of knowledge on seed recovery. Seed selection was an important activity, followed by the teaching of three remedies based on agroecological ingredients to combat parasites and balance the pH of the soil.

A practical workshop on energetic medicine provided an opportunity to practice various activities on how to heal and improve quality of life through breathing exercises and the preparation of medicinal plants that help balance the body’s energy. The exchange of oral traditions and drawings enabled the participants to talk about stories from the Comuna la Esperanza territory, as well as spirits from oral tradition, such as the magic ox. This project offered a space for the Esperanza community to create their visual representations of nature and allowed for sharing, learning, meeting, giving, and receiving. The activities closed with the construction of a seed altar to spread the word and thank the space for sharing and the overall impact of the project.

Eliana Peña, Bolivia

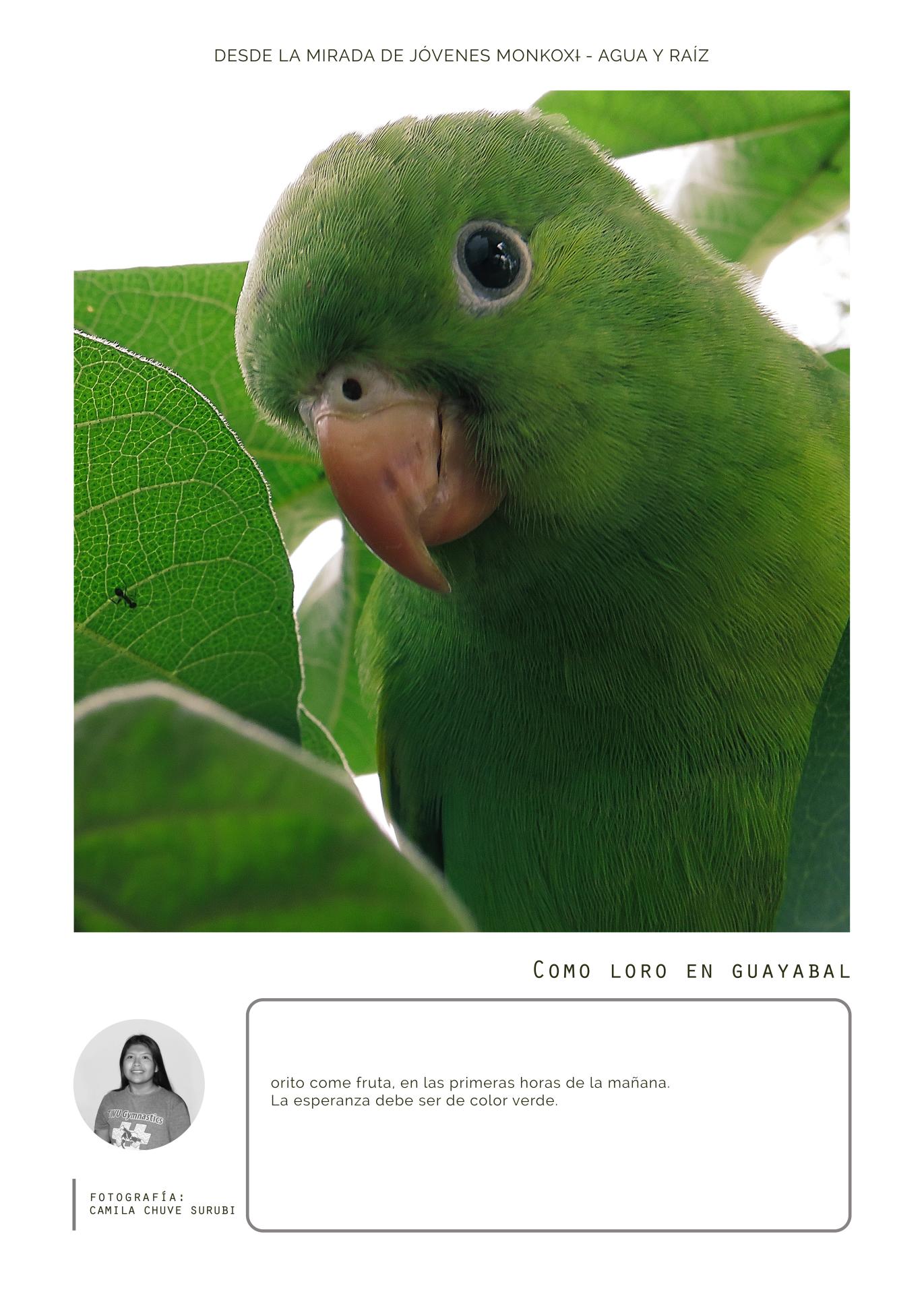

Eliana Peña (Monkoxi) was born in the community of Palmira Lomerío in Santa Cruz, Ñuflo de Chávez province, Bolivia. Her parents are Monkoxi and speak the Bésiro language. She has studied gastronomy and photography. Her project, “FotoVoz Reconexión Monkoxi,” created a photobook with young community members. Her objective is to make photography a bridge for dialogue among young people so that they can better express themselves beyond speech, through images. The project was implemented in Bolivia and aimed to build and share messages, stories, and knowledge through photography. Cultural Survival’s Youth Indigenous Fellowship was an indispensable support.

FotoVoz Reconexión Monkoxi has enabled young people to learn the basics of composition and photographic techniques, through which they depict their environment from their point of view and reality. Some youth chose to photograph their relationship to the environment and water, while others focused on the construction of legends and traditional stories of the community. Eliana Peña emphasizes that lka photography captures moments from their own point of view, enabling others to see what they feel and appreciate.

In addition, FotoVoz Reconexión Monkoxi enabled young people to express their opinions and positions in decision-making, reinforcing a new mode of communication beyond words. Many young people found it easier to express a message in a photograph than in writing or speech. This project was documented, shared, and distributed to other Indigenous youth in the hope of replicating the methodology in other communities.