Indigenous Language Journalism in Nepal: A Vital But Challenged Landscape

20 Juli 2024agnes

By Dev Kumar Sunuwar (Koĩts-Sunuwar, CS Staff)

As the world grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for accurate information became crucial for safety, infection management, and accessing essential services. In Nepal, a linguistically diverse nation, relying on a single language and medium proved insufficient. The misconception that all Nepalese were fluent in Nepali meant life-saving messages bypassed many Indigenous communities. Limited comprehension of Nepali makes these communities vulnerable to misinformation circulating online and via social media. Even Kathmandu, the capital, was not immune to rumors fueled by a lack of reliable information. In remote villages, language barriers exacerbated confusion, anxiety, and ill-preparedness, leading to dangerous misconceptions, such as believing alcohol could cure the virus.

Indigenous communities, often lacking literacy in Nepali or English and having their own languages, were particularly disadvantaged. Essential terms like “trafficking,” “social distancing,” “mental health,” and “virus” lacked direct translations. The Indigenous Media Foundation faced similar challenges earlier, translating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) into 41 languages for the UN library. Translating the ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into 22 different Indigenous languages encountered similar hurdles. Symbolic words became essential for journalists to bridge the gap, highlighting the importance of delivering information.

Nepal, a nation rich in cultural tapestries and diverse languages, faces a significant communication barrier for Indigenous communities. Despite making up roughly 35 percent of the population, these groups often struggle to access crucial information due to the dominance of Nepali and English in mainstream media. The consequences of this information gap can be severe. Vital public health messages about pandemics or mental health awareness can be lost in translation, leaving Indigenous communities vulnerable. Similarly, crucial environmental discussions concerning the “green transition” or the “green economy” impacting Indigenous lands and territories might be inaccessible. Indigenous language journalism offers a powerful solution. By delivering news and information in familiar tongues, journalists can empower these communities. They can ensure vital public health information reaches the most vulnerable, fostering informed decision-making on issues affecting their lives. Additionally, Indigenous journalists play a crucial role as watchdogs, holding authorities accountable and ensuring Indigenous voices are heard on issues like environmental protection and resource management.

A Rich History of Indigenous Language Journalism

Nepal’s media landscape boasts a rich history intertwined with the country’s political evolution. The journey began in 1896 with the publication of Gorkha Bharat Jeewan, the first Nepali-language magazine, in Banaras, India. In 1901, the Rana dynasty established the government-run Gorkhapatra newspaper, but general public participation and access to the media was restricted. The newspaper served as a mouthpiece for the rulers rather than a platform for public voice.

Indigenous language journalism faced a more challenging path. The first attempt came in 1925 with Buddha Dharma Ra Nepal Bhasa (“Buddhism and Nepalbhasa”), a Nepalbhasa (Newari language) magazine published in Calcutta, India. Though short-lived, with only 19 issues, it played a significant role in reviving the Newari language. However, the Rana regime’s suppression of free speech extended to Indigenous language publications, leading to the arrest of the magazine’s publisher, Dharmaditya Dharmacharya, in 1990.

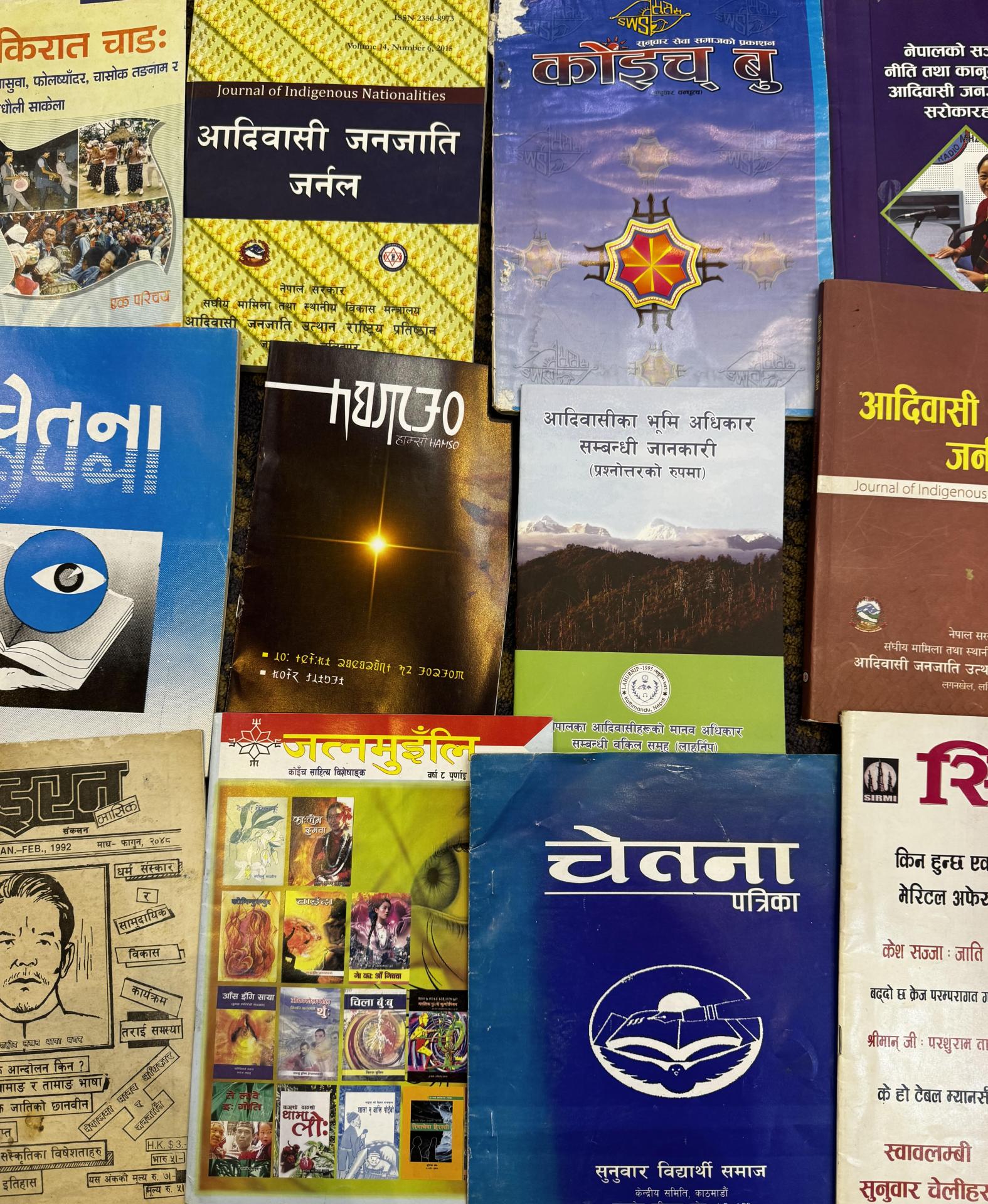

The true flourishing of Indigenous language journalism arrived with the restoration of democracy in 1990. The Interim Constitution guaranteed freedom of expression and publication, empowering various Indigenous communities to establish their own newspapers and magazines. Many publications emerged in languages like Nepalbhasa, Tharu, Tamang, Limbu, Magar, and Gurung. At one point, over 2600 newspapers were registered for publication in multiple languages.

However, this surge faced its own challenges. Many publications struggled to find long-term financial support and eventually ceased operations. Government data paints a concerning picture: except for Nepalbhasa publications, most Indigenous language newspapers have become virtually extinct. Today, only 21 Indigenous language newspapers survive, including Nepal Bhasa Times, Lahana, and Jwajalapa (Nepalbhasa), Tamang Dajang and Tamsaling Kayi (Tamang), and Tanchhopa (Limbu). A few newspapers in Rai languages like Chamling, Bantawa, and Wambule remain, but their numbers are dwindling.

Financial constraints, limited reach, and a lack of business acumen have contributed to their decline. Discriminatory state policies and restricted access to government services further marginalize Indigenous language media. Media advocating for Indigenous rights face hostility, and a lack of advertising revenue hampers their sustainability. Inconsistent editorial quality and low readership within Indigenous communities exacerbate these challenges.

The Importance of Indigenous Language Media

Nepal, with over 124 languages, faces challenges in its media landscape. Dominant languages like Nepali are privileged in education, governance, and media. This marginalizes Indigenous languages, hindering their development and potentially leading to endangerment. Ironically, information dissemination, a core function of media, is hampered when it excludes the very communities it aims to reach.

A glimmer of hope emerges with the growth of Indigenous language media outlets like the non-profit Indigenous Television. Broadcasting in over 18 Indigenous languages, member radios of the Indigenous Community Radio Network produce news and programs in 38 different languages. These provide a platform for Indigenous stories and perspectives. However, significant challenges remain. The number of Indigenous journalists working in these outlets is considerably lower compared to other communities. Moreover, a concerning lack of female representation exists within Indigenous journalism.

Investing in Indigenous-language journalism goes beyond inclusivity; it’s about empowering a substantial portion of Nepal’s population. By fostering a network of well-trained Indigenous journalists and supporting media outlets broadcasting in local languages, Nepal can bridge the information gap and ensure its Indigenous communities are informed, engaged, and empowered.

A Call for Reform and Action

Indigenous working journalists in Nepal are urging reform of media laws at all levels—federal, provincial, and local. They argue that current policies don’t adequately support journalism in their native languages. Senior journalist Ganesh Rai emphasizes the importance of the mother tongue for Indigenous identity. He argued that classifying Indigenous media differently would address many challenges they face. Rai painted a grim picture of the current state of mother-tongue journalism in Nepal. He stressed the need for policies that encourage this form of media, which he sees as a vital tool for marginalized communities to have their voices heard. Specifically, Rai called for amendments to media-related bills currently under consideration by the federal parliament. These include the Media Council Bill, the Mass Media Bill, and the Social Media Bill. He wants these bills to be more inclusive of tribal media.

Rewati Sapkota, press registrar for the Bagmati Province government, acknowledges the crucial role media plays in language revitalization. “We embarked on this journey to be the first provincial government to welcome Indigenous languages into official business,” he explains. “Now, we are looking to promote them further in education, media, and the judiciary.”

Sapkota emphasizes the importance of collaboration: “We’re open to suggestions from all stakeholders to promote Indigenous languages, especially within the media. Media platforms provide a space for the best use of these languages. By seeing, watching, and listening to programs, young people and communities are encouraged to use their languages at home and within their communities. Promoting languages in media is one of the best ways to ensure their continued use, alongside education initiatives.”

The Future of Indigenous Language Journalism

Nepal’s media landscape is vast, with a staggering number of registered newspapers: 7,835, 243 television stations, and 1,186 FM radio stations. Despite this abundance, Indigenous language media remains a minority. Only 21 newspapers cater to Indigenous communities, alongside a handful of FM radio stations (around two dozen) and at least six television channels. These include prominent names like Indigenous Television, ITV Nepal, Newa TV, Janasanchar, Nepa HD, and Nepal Mandal Television.

Looking ahead, the focus will be on integrating Indigenous languages into various aspects of daily life. This multi-pronged approach, encompassing government policies, media initiatives, and educational programs, offers a promising path for the preservation and promotion of Nepal’s rich linguistic heritage.

The growing recognition of Indigenous languages in Nepal’s media landscape represents a positive step towards inclusivity and cultural preservation. However, significant challenges remain. Expanding media coverage in Indigenous languages requires sustained government support, increased private sector participation, and innovative technological solutions. By working together, stakeholders can ensure that the rich tapestry of Indigenous languages in Nepal continues to thrive in the digital age.

For journalists working in mainstream media, adhering to journalistic norms and ethical codes might seem sufficient. However, Suresh Kiran Shrestha, a member of Nepal’s Language Commission, argues that Indigenous language journalism carries a far greater weight. “While following journalistic ethics is essential,” Shrestha emphasizes, “Indigenous language journalists need different skills.”

This specialized skill set goes beyond simply reporting the news. “Their role is to promote, protect, and revitalize Indigenous languages,” Shrestha explains. This means making information and communication content accessible in the languages their communities understand. It requires sensitivity and a proactive approach.”

Shrestha highlights the crucial role Indigenous language journalists play in bridging the knowledge gap. “They don’t just bring knowledge to the public in the languages of Indigenous Peoples,” he says, “Indigenous media and practitioners have been instrumental in protecting and promoting these languages. Media is, without a doubt, the most effective tool for language preservation.”

Shrestha proposes a paradigm shift. “The popular slogan has long been ‘communication for development,'” he observes, “but now we need to work towards ‘communication for language preservation.’” To achieve this, Shrestha calls for immediate action. “The press council or the department of information and communication needs to establish an Indigenous Language Media Department right away,” he urges. “Without dedicated support for Indigenous language media practitioners and journalists, there’s a real risk that these vital platforms could become a thing of the past.”

Shrestha’s message is clear: Indigenous language journalism is about more than just reporting the news. It’s about safeguarding the cultural heritage and identity of communities. By promoting and revitalizing these languages, Indigenous language journalists are ensuring that future generations can connect with their roots and traditions.

Establishing an Indigenous Language Media Department, as Shrestha proposes, would be a significant step towards achieving this goal. By providing dedicated support and resources, such a department could empower Indigenous language media practitioners to continue their vital work. This, in turn, would ensure the languages they champion continue to thrive for generations to come.

The decline of Indigenous language media raises concerns about the preservation of these languages and access to information for these communities. Promoting Indigenous languages through media requires a multi-pronged approach. The government can develop policies promoting media usage of Indigenous languages, media houses can prioritize content creation in these languages, and educational institutions can introduce courses focused on preserving and promoting Indigenous languages.

By working together, stakeholders can ensure that Nepal’s rich linguistic tapestry remains vibrant. Investing in Indigenous-language journalism empowers a substantial portion of Nepal’s population, fostering a sense of pride, identity, and cultural continuity. In a world where globalization threatens linguistic diversity, Nepal’s efforts offer a compelling model for empowering Indigenous communities to safeguard their languages and ensure their voices are heard. This aligns perfectly with Article 16 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which Nepal has ratified. The article affirms the right of Indigenous communities to establish their own media and access non-indigenous media without discrimination. It further encourages states to ensure media reflects cultural diversity. By supporting Indigenous language journalism, Nepal is upholding this crucial international commitment.