CONSERVING LAND FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

6 September 2018intern

Thu, 09/06/2018 – 09:26

Native Land Conservancy (NLC), based in Mashpee, MA, describes itself as the first Native-led land trust east of the Mississippi, with a mission “to protect sacred spaces, habitat areas for our winged and four-legged neighbors, and other essential ecosystem resources to benefit Mother Earth and all human beings.” Founded in 2012 by Ramona “Nosapocket” Peters (Mashpee Wampanoag) with startup grants from Fields Pond Foundation and the Island Foundation on the principle that all land is sacred, NLC aims to partner with other land conservancies, provide Indigenous wisdom to protecting natural resources, and have an interest in protecting ancient village sites, planting grounds, and hunting and fishing campsites of their ancestors.

Native Land Conservancy organizes annual events to highlight Eastern Woodlands Native American cultures and histories of the lands they are preserving through activities such as co-walking adventures, which are open to the public. Other projects include canoe trips following traditional Wampanoag and Nipmuc water routes, as well as the annual Herring Run Clean Up, organized before the ceremony to welcome the herring coming in upstream.

Native Land Conservancy’s current land holdings are located in Sandwich and Barnstable, MA and several more are in the process of negotiation. In an effort to gain more access to places of cultural significance and inspire local oral traditions to preserve land stories, NLC also has been negotiating cultural respect agreements with local communities and other land conservancies. The agreement with the town of Dennis, MA, signed between NLC and Dennis Conservation Trust, was the first of its kind in the Eastern U.S., and allows NLC to conduct cultural practices on the land.

Cultural Survival recently spoke with Ramona Peters, NLC founder and chair, former Cultural Survival board member, and Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal historic preservation officer.

Cultural Survival: How is the Native Land Conservancy different from other conservancies, and what is unique about the Indigenous approach to conservation?

Ramona Peters: Giving land back to Indigenous care sends a powerful message. There is a lack of diversity in the national land trust community, and NLC is the only Indigenous land trust in Massachusetts. We are Native-run, meaning the board of directors will always be Native and will help assure that an Indigenous perspective on land use and management is exercised on lands we protect. The opportunity to serve on the NLC board is open to all Tribes, while membership to the Conservancy is open to everyone, Indigenous or not.

We have spent most of our lives outdoors along the rivers, bays, pine woods, and knolls. We were instructed by our elders to regard all living things with respect. We are blessed with amazing treasures; plants, minerals, and animals that have offered medicine and food to our people for thousands of years. Cultural differences are to be expected, but the disconnect between Western science and traditional knowledge has caused the land to be abused. Characterization of plant life only around what benefits humans can derive reminds me that Westerners have been charged with the mission to dominate the earth through the 1452 papal bull of Pope Nicholas V. Worldview obviously shapes a culture and individuals, so we shouldn’t ignore what has happened to this continent since colonization. Thankfully, some walk to a different beat. There’s heavy politics and capitalism running through the framework of American land conservation. The privileges of time and money have eluded most of us to even sit at the table to listen. We’re grateful that there are still vast amounts of protected acreage living safely, despite the varied motivations to conserve.

CS: What are some of the projects you have worked on?

RP: The most exciting project we’re accomplishing is rescuing the ancient Wampanoag Muttock-Pauwating village site in Middleborough, MA, which contains evidence of Indigenous occupation dating to as many as 7,500 years ago. The site is essentially still intact, and represents a powerful and sacred place to the Wampanoag. This is the second time that the NLC has committed significant funds toward the purchase of a property for preservation. About 12 or 13 years ago during the beginning stages of a housing development, artifacts and 3 burials were discovered. Eventually the village footprint was uncovered and 56,000 artifacts were removed. It’s taken an enormous effort to raise the funds to protect this village site from total annihilation. The town of Middleborough, NLC, and the Archaeological Conservancy are each contributing over $100,000 toward the rescue. We’re closing on the purchase at the end of August.

We’ve also hosted students from UMass Boston Women’s and Gender Studies and Environmental Studies programs to help with cleanups in the Spring. It’s been a very positive experience to work alongside college students that come from different parts of the country. And we’re kicking off the canoe trips in Wakeby Lake (Mashpee Pond). Cape Cod is pretty fragile—we’re basically like a sand dune sticking out into the Atlantic. We’d like to bring greater awareness about the springs and the fresh water under the Cape. If the lens of fresh water gets punctured by salt water, or if it gets polluted, there’s nothing we’ll be able to do to recover. Cape Cod is a world renowned location that has a lot of unwise and untidy visitors who stay for a month or two during the summer. We know we have to take protective measures and offer educational outings.

NLC is also interested in protecting land outside of Cape Cod. We’re finding ways for Native people to have access to special locations that may have been village sites or ceremonial grounds. Sometimes we know there are cultural features on privately owned land and we want to be able to go there as a group. If there are cultural resources there, like different medicinal plants or renewable resources that we’d like to be able to forage for, or harvest seeds, we want to do that as well. When it comes to land reclamation practices, planting indigenous seeds is something we are interested in doing. The lack of indigenous grasses has created a lack of habitat for the quail, partridge, and pheasants that used to be our neighbors. By vacuuming up indigenous seeds wherever we can find them, we can then spread them in our reclamation projects.

Our first donation was a white pine forest, Qâqunôhqus‘ee K‘âut (Tall Pine Tree Place), in Centerville, MA. One of our male board members takes men there to connect with these specific trees. White Pine has a great medicinal effect on men that need some energetic smoothing out when they are nervous or experiencing hostile feelings.

CS: What kind of work have you done with other New England Tribes?

RP: We were recently invited to the University of Maine to talk about our cultural respect agreements with the Wabanaki Confederacy of Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Abenaki. Many Tribes in Maine still subsistence hunt and fish. As far as hunting goes, you go where the animals are, but they can’t always do that because of properties being private or owned by conservation groups. Since that’s true, they could craft a similar agreement as ours to gain access to hunting grounds. A cultural respect agreement can be made, especially if they’re interested in going where petroglyphs are for ceremony or educational purposes.

I have seen a Penobscot map that showed dozens of special land spaces that had incredible stories attached to them. I remember a story that talked about a place where a hungry human being first learned how to make arrows for hunting from a magical creature—the story eventually leads you to a quarry where the superior rock for arrowheads is located. It’s pretty amazing. Of course, we also talked about the dangers of putting exact locations of sacred places on a map where people could find them and do harm.

CS: What are some of the challenges you have faced?

RP: When land is put into a conservancy, it becomes public land for light recreation so you can walk the trails. When we go as Native people to do a ceremony, go blueberry picking as a big family, or if we go scalloping or to gather beach plums, we attract attention. The last thing we want is to have a ceremony disrupted by police or for our children to witness racism in action. This is why it’s become necessary and important to have a cultural respect agreement, for special access to the property even if it’s open to the “public.” The unreasonable fear of seeing brown people in the woods is something that I have had to talk openly about among land trusts. Our first cultural respect agreement at Chase Garden Creek in Dennis gives us access to 250 acres of marshland. This agreement is only for five years because the majority of their board members were wary of having an agreement with Indian people. This tells us we need to mingle more with our allies It’s easy to stay within our comfort zone among our own people, but this behavior has contributed to ignorance and fear.

For example, an elderly woman in South Mashpee wanted to bequeath her land on one of the small islands to NLC. Shortly after she informed her neighbors, she got emails and phone calls from them telling her to not allow Indians on the island. The emails said that she shouldn’t trust us, that it would draw more of us around their houses, and the ridiculous notion that we’d build a casino on the island. We are a land conservation group; that’s our whole purpose, but people are ignorant about this. She was going to stay with us all the way regardless of her neighbors, but we had to drop the effort after we were warned that the town selectmen were going to vote against allowing her to have a conservation easement. I attempted to engage with members of the board of selectmen. Three of them were actually hostile to me; another wouldn’t respond at all. We have had to face some powerful racism. I wasn’t expecting that level of abuse of power from Mashpee town officials. We had a similar experience in the town of Yarmouth when we offered $50,000 to help their local land trust purchase a parcel that we see as culturally significant and the town officials declined to accept our involvement.

CS: What is next for the Native Land Conservancy?

RP: Within six months we’re going to gain four more parcels of land of varying sizes from different towns. We’ve been promised a wetlands area in Yarmouth, which has cultural and historical value. Two weeks ago we received a bequeathment to a Cotuit property with a small cottage. There are five different organizations looking to make cultural respect agreements with us. We also hope to get off the Cape a little more with the land acquisition. We need more visibility. We’d like to exist as an organization for at least 500 years into the future.

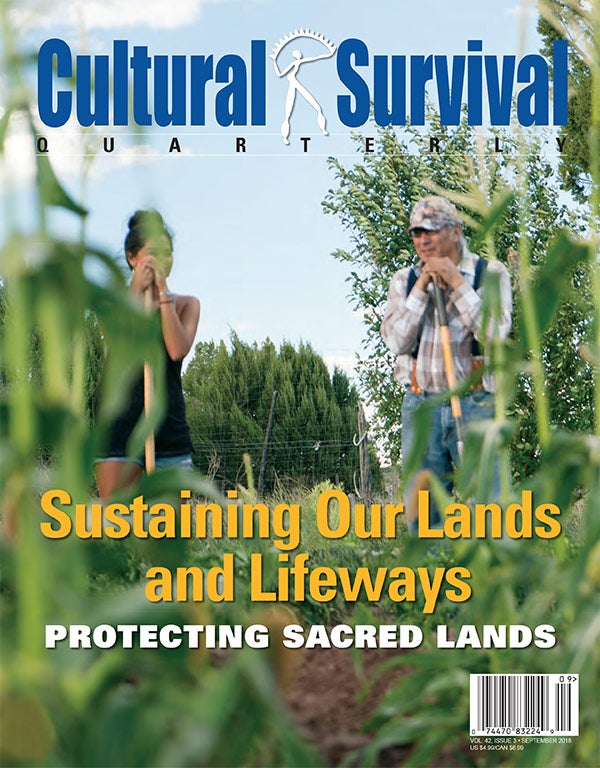

Photo Credit:

Photo courtesy of Native Land Conservancy.