Reflecting on Being Cultural Survival’s First Indigenous Leader

2 Juni 2019intern

Sun, 06/02/2019 – 12:02

For the past eight years, Suzanne Benally (Santa Clara Tewa and Navajo) has served as Cultural Survival’s first Indigenous executive director. She has played a vital role in the development and success of the organization, bringing critical insight and experience needed to understand and promote the self-determination and rights of Indigenous Peoples. Under her leadership, Cultural Survival has strengthened its advocacy of the rights of Indigenous Peoples while expanding and developing community-based programming in Indigenous and human rights work internationally.

We feel honored and fortunate to have worked under Benally’s leadership, and we are grateful for her wisdom, compassion, and stewardship of our organization. Before her departure, we sat down with Benally to get her final thoughts on her tenure at Cultural Survival.

Tell us about your experience being an Indigenous woman executive director.

As an Indigenous woman leader, I tend to think about my leadership as a holistic, carefully deliberate, and an interconnected process that is dependent on others; I think of this as a cultural form of leadership. It is challenging to practice this style of leadership in a mainstream, non-Indigenous organization, because it requires negotiating different values and helping people understand a new kind of leadership and ethos that reflect the communities we serve. That’s perhaps the most important challenge as I clarified the vision and mission of Cultural Survival, and as the staff, Board, and I discussed how we would move it forward. I overcame these challenges by intentionally working with the staff to see themselves as part of the vision, and helping them acquire the kind of knowledge and understanding that is needed to do that.

Indigenous women still need to be recognized for the roles that they have in leadership. We need to hear more of their stories. Indigenous women in many cultures are recognized as leaders, but over time colonization diminished that. Today it is about intentionally providing the access, naming issues of inequity, recognizing our roles in maintaining the patriarchy, and doing something about it. It requires deliberate action: cultivating women into particular leadership roles in our search practices, reaching out and tapping Indigenous women for these jobs, and providing the kind of support for Indigenous women leaders to fully be realized. We also have to rethink how we define leadership and the criteria needed for leadership.

What led you to leave academia for the Indigenous rights world?

I’ve always had an interest in international Indigenous voices, policy, and UN level work. Early in my career I began to read about the early UN meetings and marches into Geneva and Indigenous Peoples trying to gain access and recognition by the UN. I grew up on the Navajo reservation witnessing the building of coal fired power plants that required coal mines to supply them, the devastation of uranium mining, the environmental and health impacts, the shift in community life, and the blatant racism. In my graduate work I was researching emerging literacies as political and resistance acts to colonization around the world, especially in Indigenous communities. Growing up in a community where all these issues are alive made me want to be on the ground doing the work and not just in a college classroom teaching about it.

How have you seen the Indigenous rights movement change over the past eight years?

Certainly the increasing recognition of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, increasing engagement of those rights through UN bodies and agencies, NGOs, and others, and the increased naming and assertion of Indigenous rights as outlined in the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. I also know that resistance and struggles on the ground were already occurring, and continue to occur, outside the parameters of the UN efforts. What concerns me is that the movement doesn’t get bogged down in a UN bureaucratic process and become yet another kind of bureaucracy we have to deal with. Implementing the Declaration is important, and for that reason Cultural Survival got behind it as well as other UN efforts. But there has to be national and international policy impact, and Indigenous Peoples have to be able to benefit from it. This calls for Indigenous communities to be active in community, regional, and State levels to force change. The presence of the international movement of Indigenous Peoples is significant and dynamic.

Can you speak a bit about your strong focus on promoting and developing Indigenous women’s and youth leadership? This has been a main thread across all of Cultural Survival’s work under your leadership.

It is important that we address Indigenous women. We should honor women as leaders in their communities, whether they’re mothers, grandmothers, aunties, community workers, or professional women. Women provide key leadership for ensuring the well being and health of families, communities, and societies. Their roles as leaders are too often diminished, if not crushed entirely, because of sexist beliefs, attitudes towards women, and issues of gender equity. We see this reflected in the crisis of violence against Indigenous women. We have to heal from the colonizing forces that are the root of this, and we have to stand up to the practices that continue to oppress women. If we want to have healthy communities and societies, it is an imperative to pay attention and act on behalf of the well being and health of women and children. I felt Cultural Survival should address these issues at the center of all its programs, and we set out to do that.

In terms of youth leadership, youth are the future, they are the next generation of leaders; this is the world that they inherit. It is extremely important that we address their needs and concerns, that we are nurturing their future leadership and involving them in the solutions. Youth have so many new innovative ideas. They best understand the contemporary world they live in and experience its joys, pains, and concerns. We need to listen to them and offer our wisdom and support as they design and build their futures. I like the way in which we are supporting youth engagement at Cultural Survival through our Youth Fellowship program.

What do you see as the most pressing issues that need to be addressed?

Indigenous community media is one important area to assure freedom of expression and inclusion. We need the presence of voices of Indigenous people speaking for themselves, in their own languages, generating news along with the stories of their needs and successes, issues, and concerns. The access we provide to rural communities, the ways in which we try to be a bridge for information flow between the policy level to the ground level and vice versa is extremely important. Also important are thriving Indigenous languages, which are critically important to sustaining cultures. Our spiritual understandings and instructions were given to us in our languages.

Since the beginning, you have been passionate about environmental work and Traditional Knowledge. What role can Cultural Survival play in promoting Indigenous voices for environmental protection?

The issues of climate change, climate justice, and the environment are all top priorities and some of the most important issues of our time; especially the accelerated rate that we’re seeing the impact and changes, losing communities and whole cultures as a result. There is a lot of work being done by Indigenous communities on climate change in many different venues, so ways in which all of that can be brought together and discussed is important. How we enter the conversation at the policy level is also critical. We often receive invitations to share our wisdom and knowledge, but it is much more complex than that. From a Western perspective, it’s like, ‘give us what you have, give us your solutions.’ How we enter these dialogues and relationships is important. We need to be able to influence policy. We need to talk about the solutions that we are practicing, and how they are based with relationships with the natural world. You simply cannot take those solutions and transplant them into a new, unrelated context. We also need to recognize the potential of integrating Western science as part of the solutions. How this translates into policy is going to be important, and more importantly how it translates into practice. You cannot just take and use Indigenous cultural practices if you do not have the cultural context to hold them; it is fundamentally asking for a complete shift of how we exist on this earth.

Much needs understanding: how do we share our wisdom and our knowledge to be effective for all humankind? At the policy tables, there are Indigenous people pushing for understanding and demanding to be part of the conversations. We need to have access to those conversations. We have our Indigenous science, our traditional ways of knowing, and we have life. For our survival, we need to be heard along those lines. Cultural Survival can be a convener for those conversations and a disseminator of the information.

Final reflections: You are highly valued by Cultural Survival Board and staff and will be deeply missed. What is next for you?

It has been an amazing learning experience and journey and an incredible honor to work with Cultural Survival. I remember my first year, feeling so humbled by what I did not know about Indigenous Peoples across the world. The fight for Indigenous rights has been very important work to me. Doing this work through an organization such as Cultural Survival was rewarding and I plan to continue in other capacities. I am exploring next options and thinking about how to continue this work at a local level within my community, because there is such need.

I plan to take a deep breath and a long exhale and move forward. I will continue to support Cultural Survival and be involved. I could not have done this job without the amazing and dedicated staff. I am proud of what we have done. I began this interview talking about the challenges of being an Indigenous leader at a non-Indigenous organization, I want to recognize the staff for their good work, learning, and support. I would also like to recognize the incredible Board; their support and leadership has been very important to me. In addition, thank you to the many friends and allies of Cultural Survival for their support. We are all part of the leadership!

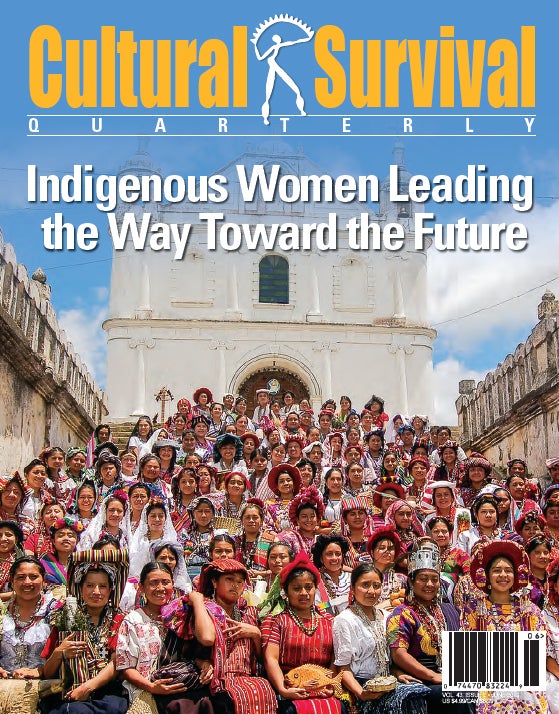

Top photo: Suzanne Benally (center in black) with Cultural Survival

Staff, Board, and Youth Fellows. Photo by Jamie Malcolm-Brown.