Refugees After Crossing the Imaginary Limit

12 Maret 2020

12 Maret 2020

agnes

Sat, 03/07/2020 – 11:12

Angela, a 75-year-old Wayúu woman, with her husky voice and slow steps, runs through the courtyards of her new shelter made up of plastic bags and zinc sheets that she, her family, and neighbors call her new home. It has been more than two years since they came to the ranchería that they named Perra’a (or Vera, a common tree in the mountains of La Guajira). This small refuge is located a few kilometers from Paraguachon on the road to Maicao, Colombia. Entire families migrate to the other side of the Venezuelan and Colombian border in search of refuge from hunger and violence that took over their ancestral lands. There they still suffer from hunger and indifference of State governments that have been imposed over the Wayúu traditional territory.

Along with Angela, more than 40 families came, numbering almost 200 people including children, elderly, and pregnant women, who, in search of better living conditions, now share this small space of about 2 square kilometers. Their places of origin are Calie, Caujarito, and La Frontera communities that are a little less than 8 kilometers away on the Venezuelan side of the border. Their goal after emigrating is survival and finding better living conditions than they faced in their communities of origins where armed forces and military groups imposed their laws to strip Indigenous Peoples of their territories.

The Wayúu Nation are one of largest Indigenous Tribes in Colombia and Venezuela, with more than 20 clans. About 95 percent of the population speak Wayúunaiki, and only 30 percent speak Spanish—so communication becomes a barrier when attempting to access education, medical, and legal services. According to data from the Administrative Registry of Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia, in 2018, in a span of just 6 months, 74,874 migrants arrived in La Guajira, with a total of 26,579 who recognized themselves as Indigenous from Venezuela. An exact number cannot be determined due to lack of documentation, but as the number of migrants continues to increase, Wayúu continue to face challenges of language and identity loss and a dramatic deterioration of their cultural structures.

Known as the people of the sun, sand, and wind, the Wayúu Nation has been divided by the Venezuela and Colombia border since the early 18th century where negotiations began to divide the Guajira peninsula. Their traditional lands cover approximately 23,000 square kilometers, of which 80 percent is on the Colombia side and about 20 percent in Venezuela. La Guajira is located in the northern part of Colombia and northwest of Venezuela in the state of Zuila. Although known as La Guajira in the Wayúunaiki language, the word Guajira does not exist and is known among the Wayúu Nation as Woumainru´u. The word originated from Goahire, or Goshire, which in Wayúunaiki means “land swept by the wind” and was used for the first time in the Spanish maps of South America that were published in 1527 and 1529 in reference to Wayúu territory.

Wayúu people were never subjugated by the Spanish empire and demonstrated resistance with the Indigenous uprising during the 17th century. This led to an ongoing dispute of the Guajira peninsula between Colombia and Venezuela until both countries received independence from the Spanish empire in the late 18th century and the Wayúu Nation became free from both borders. Today they occupy 6,710 square kilometers of the harsh environment of the La Guajira desert throughout Colombia and Venezuela.

Although the Wayúu were able to achieve self-governance, they have faced discrimination and exclusion from both State governments, each violating their rights and extracting raw materials from their lands. Their territory is no longer the same; the judicial and legal territory has no harmony with the historical sociocultural ways of the Wayúu Nation. To the Wayúu,territory has been without limits—one of the primary elementsof their culture is to come and go freely. However, their modern confinement to La Guajira creates an imbalance of their living space. It is part of the tradition and custom of the Wayúu Nation to remain with the land in a multidisciplinary way with the purpose of protecting their ancestral lineage in order to sustain future generations.

Recent migrant Carmen Sapuana says, “Crossing to these lands, we have been well received here. But it is not the same because we do not have what we really want: the freedom to walk in our territory as we deserve. I know that this is ours because the limits were invented by the Creoles to mark one country from the other. The Wayúu are scattered in this wide territory that we recognize as the great Wayúu Nation.” Sapuana adds that her worst fear after fleeing her community was losing the essence of what created her children.

Communities have been dependent on farming, creating crafts, and, in the coastal communities, pearl diving. However, climate change has impacted sustainable farming practices with droughts, threatening crops and dehydration among the animals. The commercialization of pearl diving has also threatened communities’ aquaculture. Due to these factors, many have abandoned these traditional practices and are having to find other means to sustain their basic needs. This has led to criminalization and increased alcoholism, especially among the males in La Guajira. In Venezuela, the Wayúu relied on subsidized groceries by the government, but due to instability in the country much of this assistance has stopped, causing malnutrition throughout communities. This has led to many families abandoning their homes in Venezuela in search of a better life in Colombia with hopes of returning someday. Learning to live together has not been easy, and there is a great desire among Wayúu migrants to return to their homelands and live like they used to. They remember how difficult it has been to unexpectedly change their way of life, and this makes their yearning to return to their ancestral lands multiply. “I wanted to be a nurse and get my children ahead, but here I am,” says Paola Vanesa González. “I have nothing.Just the desire to continue living and only faith helps me. We are certain that one day this will improve. Venezuela hurts us because we were born and grew up there and our memories stayed.”

Arriving at this new home has forced the migrants to detach from many things that rooted them in their ancestral territories, in sacred places such as cemeteries, conucos plots of land that Indigenous people cultivate), and even their childhood memories. González, 29, said she feels like she is living in a vacuum after leaving her territory and everything behind. “We left many things we wanted; our house, our animals. People took advantage of those after our absence. I also left my 72-year-old grandmother. I left her because she didn’t want to come, telling us that there isn’t enough space here for her and because she is used to more open places like on our traditional lands,” she said.

The migrants affirm that it has been hard to survive, and even though they claim to be safer than in Venezuela, they do not lose hope of that moment of returning to their home—the one where they were born and from which they never wanted to leave. To abandon one’s home is to abandon one’s essence. “Sometimes I wonder what will happen to us,” Angela said. “Will we get used to this place? Or maybe one day we will return home. I really do not know if I will get to see that day, or maybe it is my children or my children’s grandchildren. I don’t know; only God knows what will happen.”

— Ronald José Fernández Epieyuu (Wayúu) is a 2019 Cultural Survival Indigenous Youth Community Media Fellow. He is a community journalist from Utay Stereo in Guajira, Colombia.

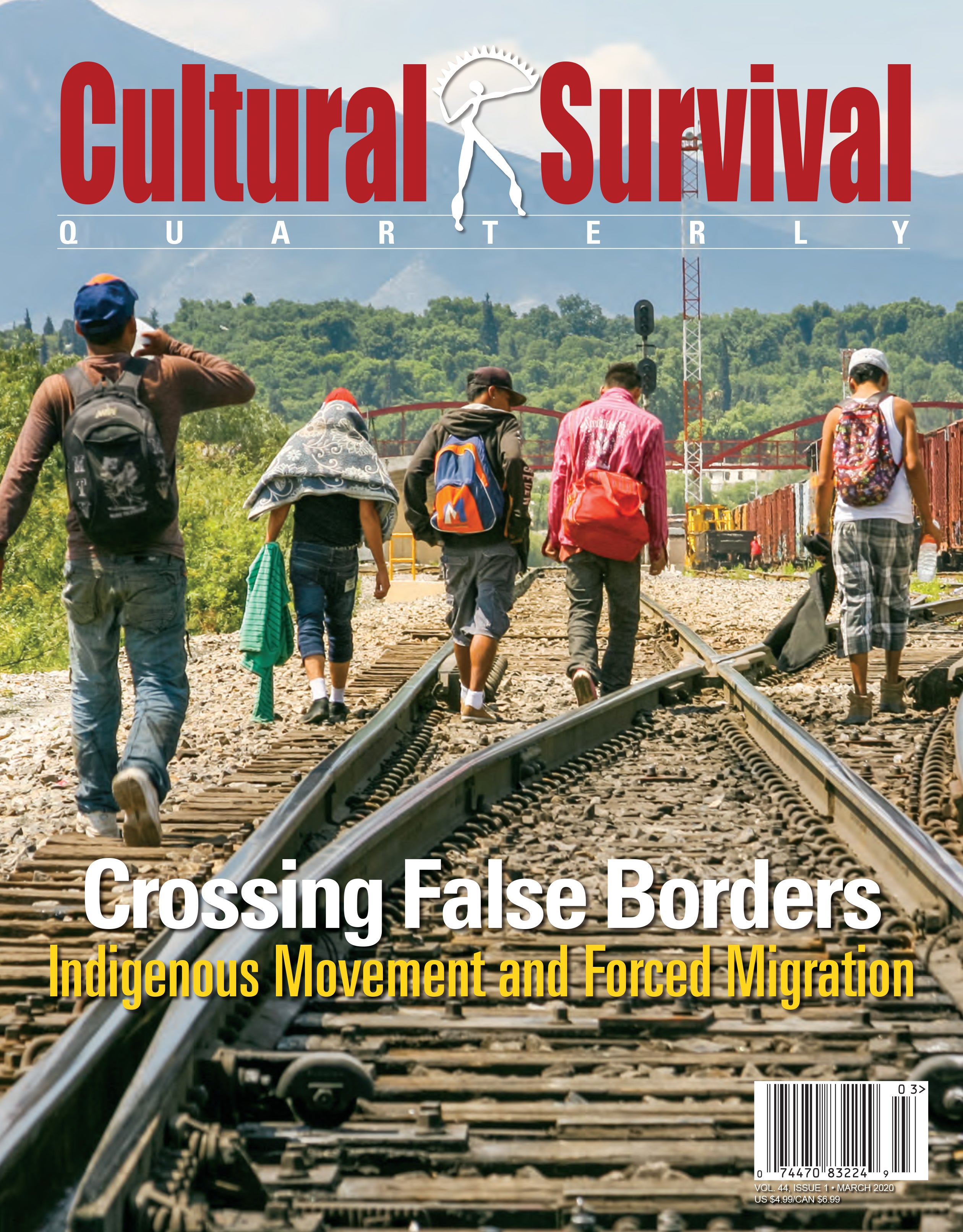

Top photo: Wayúu migrants from Venezuela, surviving in ranchería Perra’a, near Maicao, Colombia.