The Plight of Haiti

30 September 2021

30 September 2021

By Jan Lundius

STOCKHOLM / ROME, Sep 30 2021 (IPS)

I assume channel surfing and internet browsing contribute to a decrease in people’s attention span. I am not familiar with any scientific proof, though while working as a teacher I found that some students may be exhausted when five minutes of a lesson has passed and begin fingering on their smartphones. They might also complain if a text is longer than half a page, while finding it almost impossible to read a book.

Maybe we are all incapable of keeping a focus. For a while, Afghanistan overshadowed the media stream, though interest faded when the tragic scenes at the airport of Kabul were not there anymore. New catastrophes await the attention of world media.

Attention to Haiti comes and disappears in short flashes. Most recently, we were regaled with pictures of how US horse-mounted patrollers by the Mexican border were roping in Haitian immigrants, reminding us of how runaway slaves were caught 150 years ago. Three days later the US special envoy to Haiti resigned in protest of an ongoing large-scale, forced repatriation of Haitian migrants to a homeland wrecked by civil strife and natural disaster. Daniel Foote was appointed after the assassination of Haiti’s president. His letter of resignation reflects a deep concern for Washington’s disinterest in improving conditions in Haiti:

“I will not be associated with the United States inhumane, counterproductive decision to deport thousands of Haitian refugees and illegal immigrants to Haiti, a country where American officials are confined to secure compounds because of the danger posed by armed gangs to daily life. Our policy approach to Haiti remains deeply flawed, and my policy recommendations have been ignored and dismissed, when not edited to project a narrative different from my own.”

The deportation of Haitians is one of the swiftest, mass expulsions ever. The US is presently receiving thousands of Afghans while sending Haitians to a country which humanitarian crisis is intimately related to earlier US interventionist policies; military occupation and meddling in internal affairs, often through support to dictators. Haiti is reeling from the 7 July assassination of its president, facing an escalation in gang violence, while some 4.4 million people, or nearly 46 per cent of its population suffer acute food insecurity. On 14 August, an earthquake shock Haiti; at least 2,200 people were killed, more than 12,200 injured, at least 137,500 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and an estimated 650,000 people are currently in need of assistance. Three days after the catastrophe a tropical storms disrupted access to water, shelter, and other basic services, while flooding and mudslides worsened the situation for already vulnerable families.

Haiti is one of the most overpopulated countries on earth. The US has a population density of 70 persons per square mile, Cuba has 235, while Haiti’s population density is almost 600 people per square mile. Agriculture is not producing enough to feed a population harassed by political instability, connected with a small, but highly influential political and economic elite, often supported by foreign stakeholders. The international community, which historically has contemplated Haiti through a lens distorted by racism and disinterest, is not doing much to mitigate a worsening situation, triggering immigration movements towards countries like the US, which government apparently assume that a solution to the problem will be to send migrants back to their misery.

Investments have to be made in education and health, as well as in support of enterprises capable of providing sustainable income, while governmental institutions need to be strengthened to promote human development for all sectors of society. Emigration cannot be the only means to brake Haiti’s chain of down-spiraling events, but it helps – currently, 35 percent of Haiti’s GDP is constituted by the roughly 3.8 billion USD worth of remittances the diaspora provides every year.

The recently murdered president, Jovenel Moïse, was originally not a member of the traditional elite, but an entrepreneur acting outside the political sphere. He developed an agricultural project of organic banana production and partnered with Mulligan Water, a US based global water treatment company, to establish a water plant for distribution of drinkable water to Haiti’s northern departments. In 2017, Moïse participated in the general elections on a platform promoting universal education and health care, as well as energy reform, rule of law, sustainable jobs, and environmental protection. He won with a slight margin. Since then, numerous roads have been built, reconstructed and paved. Haiti’s second largest hydro-power plant and several agricultural water reservoirs have been constructed, producing electricity and water for increased agricultural production.

Protests against Moïse’s regime had been mounting, among accusations of widespread corruption and a continued negligence of damages caused by the 2010 earthquake, when more than 200,000 persons were killed and 1.5 million left homeless. This natural disaster was preceded by a hurricane which in 2008 wiped out 70 percent of Haiti’s crops. In 2016, hurricane Matthew was almost as devastating.

Dangers to Moïse’s government furthermore lurked among members of the wealthy, small and powerful elite and not the least – increasingly menacing crime syndicates. Foremost among them is the one controlled by former police officer Jimmy Chérizier, alias Barbecue, leader of G9 and Family, a criminal federation of nine of the strongest gangs in Haiti’s capital.

Chérizier has been known to support Moïse’s party, Tèt Kale, and being backed by corrupt members of the police force. After being behind several armed attacks on rivaling gangs and innocent individuals, who live in fear of extortion, arson, theft and rape committed by his thugs, Chérizier has disclaimed all political affiliations and called for a ”popular uprising”, marching with his men through the slums of La Saline, while openly brandishing sophisticated weaponry.

Even if Jovenel Moïse described criminal gangs as Haiti’s “own demons”, his government’s actions have been considered as negligible. Moïse declared: “We prioritize dialogue, even in our fight with bandits and gangs. I am the president of all Haitians, the good and the bad.”

So far, 44 individuals have been arrested in connection with the assassination of Moïse, on the run is a former official in the Justice Ministry’s anti-corruption unit. Haitian police states that the killing squad consisted of 26 Colombians and two Haitian Americans. The Colombians were all former soldiers. Retired Colombian military personell are currently employed by security firms around the world, which value their training and fighting experience. Moïse’s killers were allegedly hired by an obscure, self-described doctor, Christian Sanon, through a US firm called Corporate Training Unlimited (CTU). No explanation has been given to how a man with a negligible income and 400,000 USD in debt could be the organizer of a complex and expensive plot to murder Haiti’s president. A further twist to the story is that Haiti’s interim Prime Minister, neurosurgeon and former Minister of Health, Ariel Henry, a few days ago sacked his Minister of Justice, since he supported a prosecutor who sought charges against Henry over the murder of Moïse. Everything remains shrouded in mystery.

Why Haitians turn up along the US-Mexican border is easier to explain. After the devastating earthquake in 2010, several Haitians arrived in Brazil, attracted by a building boom partly in connection with Brazil hosting the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics. When those jobs dried up, several construction workers ended up in other Latin American countries, especially Chile. Others crossed the border to the Dominican Republic, which currently host about 1 million Haitians. All over Latin America strict migration policies are now enforced, while Haitians move towards the US, fearing that misery awaits them if they return to their impoverished homeland. Some 19,000 undocumented migrants, mainly Haitians, are stuck in Colombia, trying to enter Panama and continue to Mexico, where approximately 12,000 migrants are waiting to be processed by US immigration agents, which most likely will refuse entry.

Historically speaking, the small island nation of Haiti has been important to the Americas. In 1804, it became after the US the first independent republic of the Americas. In spite of winning its war of liberation, Haiti was forced to compensate France, a debt paid until 1947. The French Saint-Domingue was one of the world’s most brutally efficient slave colonies; one-third of newly imported Africans died within a few years and a policy of ”better buy than bread” kept the slave population young and limited. After liberation an export oriented mono-cultivation of mainly sugarcane was through a land reform changed into family based small holder subsistence farming and the population increased rapidly. With an unyielding black government Haiti suffered until the 1830s of European non-recognition and it was not until the late 1860s it was accepted as a nation by the US and other American countries, while continuously being depicted as barbaric and uncivilized.

In 1822, Haiti conquered the Spanish part of the island, abolishing slavery there. The president Boyer welcomed 6,000 US former slaves, as well as political exiles from the Americas. He supplied Simón Bolívar with 1,000 rifles, munitions, supplies, a printing press, and hundreds of Haitian soldiers to support him in his effort to” free Latin America” and abolish slavery. Between 1915 and 1935 the US occupied Haiti, resulting in several thousand Haitians killed and numerous human rights violations, including torture, summary executions and forced labour. The occupation was, as has been customary with most colonial and exploitative enterprises, defended as a “civilization process”.

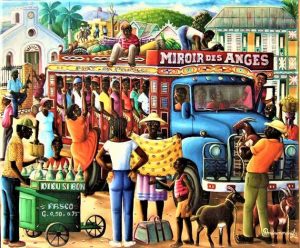

Painting, sculpture, dance and music have always flourished in Haiti. It was the Creole culture emanating among exiled Haitians in New Orleans that influenced the creation of jazz, which since then have had such a great impact on American culture. And … while listening to the depressing news about Haitian suffering it might be advisable to enjoy the works of Haiti’s great authors, like Jacques Roumain, Stephen Alexis, and René Depestre, and not the least women writers like Marie Vieux-Chauvet and Edwige Danticat. An attention span well worth the effort, particularly since it increases our knowledge of the problems harassing Haiti. Hopefully would such reading bolster the international community’s realization of the gravity of the plight of the Haitian people and contribute to end its long sufferings.