White Paper: Value-Based Safe Harbors and Exceptions to the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law

25 Februari 2021

25 Februari 2021

On 2 December 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) issued two Final Rules in conjunction with its “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care,” which will markedly change the regulatory fraud and abuse landscape for “value-based” arrangements:

(i) The HHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG) published a Final Rule that introduces new safe harbor protections under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) for certain coordinated care and risk-sharing value-based arrangements between or among clinicians, providers, suppliers, and others that squarely meet all safe harbor conditions (AKS Final Rule).

(ii) The HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published a Final Rule that finalizes similar exceptions to the Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law) for certain value-based compensation arrangements between or among physicians, providers, and suppliers (Stark Final Rule, and together with the AKS Final Rule, the Final Rules).

These Final Rules introduce an entirely new framework for structuring permissible arrangements and affiliations between and among health care providers and payors. This white paper will review this new framework and walk through the new definitions, exceptions, and safe harbors that, together, are designed to play a central role toward innovating care coordination and health care payment models for years to come.

In addition to these sweeping value-based changes, both Final Rules contain a host of other, wide-reaching regulatory changes and policy clarifications. Detailed analyses of these broad updates (outside of the value-based context) are contained in two separate K&L Gates white papers:

- Non-Value-Based Changes within the Stark Final Rule are discussed here.*

- Non-Value-Based Changes within the AKS Final Rule are discussed here.**

I. AN OVERVIEW OF VALUE-BASED CARE AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE FINAL RULES

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), HHS has made it a priority to transition away from traditional fee-for-service payment systems. This has resulted in a concerted move toward value-based models that tie provider reimbursement to increased quality, reduced costs, enhanced care coordination, and improved patient outcomes.

These concepts of the “triple-aim” or “quadruple-aim” of health care were bolstered with the introduction and adoption of the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which was authorized under Section 3022 of the ACA and implemented in 2013. Since then, CMS has tested various other innovative value-based models, often through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, refining model structures over time and focusing on a variety of provider types and clinical conditions. In addition, this value-based payment model shift was not limited to Medicare or other governmental programs. Commercial insurers have likewise taken up the mantle to shift reimbursement away from volume and toward value.

To foster this transition to value-based care, HHS promulgated various waivers of the AKS, the Stark Law, and civil monetary penalty (CMP) laws in connection with these CMS-driven innovation models. This reflected a recognition that many traditional fraud and abuse concerns, such as provider overutilization, are mitigated when payments are tied to value instead of volume.1

Prior CMS waivers, however, have been tied to specific CMS models. Value-based arrangements in the commercial setting—or otherwise outside of the scope of specifically waived Medicare and Medicaid models—remained subject to the Stark Law and AKS under a traditional regulatory analysis based on long-standing safe harbors and exceptions. These safe harbors and exceptions, however, have traditionally been ill-suited to encapsulate innovative value-based arrangements.

In 2018, HHS launched the “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care” to accelerate a transformation of the health care system, with an emphasis on eliminating “unnecessary obstacles” to coordinated care. In providing a new framework for supporting value-based arrangements, the Final Rules align with the goals of the “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care,” as HHS seeks to drive increased provider engagement with value-based care. Through the Final Rules, CMS and the OIG offer new pathways for providers and payors to come together in innovative ways, without fear of violating fraud and abuse regulations, for both governmental and nongovernmental value-based arrangements.

As this white paper will discuss, these safe harbors and exceptions are intended to cover a broad array of arrangements. In a manner of thinking, the Final Rules reflect an opportunity for payors and providers to “design their own model” through selecting, for example, the patient populations, value-based purposes and activities, quality measures, payment methodologies, referral requirements, and other components of an arrangement without these parameters being prescribed or narrowly defined. At the same time, however, CMS and OIG have included a robust set of requirements and safeguards within each of the new exceptions and safe harbors, which help ensure that the arrangements are structured to drive providers toward clear value-based goals.

For arrangements that are designed and implemented to fit within the parameters set forth in the Final Rules, providers will be able to take advantage of operating outside the purview of many traditional fraud and abuse safeguards. Of particular note, several of the new safe harbors and exceptions:

- Do not contain a requirement that an arrangement be set at fair market value.

- Do not require that compensation or other remuneration under an arrangement be set in advance.

- Do allow for directed referrals of patients to specific providers (so long as a series of conditions and exceptions are accounted for).

- Do not contain a broad prohibition on remuneration under an arrangement taking into account the volume or value or referrals.

While these flexibilities provide exciting new opportunities for payors and providers—especially when providers are prepared to take on risk—they can only be taken advantage of through careful structured arrangements that satisfy a series of requirements set forth in the Final Rules. Indeed, careful review and understanding of these requirements is, perhaps, heightened for value-based arrangements, as such arrangements may explicitly include provisions that would be expressly prohibited outside of a structured arrangement taking advantage of these value-based safe harbors and exceptions.

II. UNDERSTANDING THE FRAMEWORK OF THE VALUE-BASED SAFE HARBORS AND EXCEPTIONS

The chief focus of this white paper will be a series of three AKS safe harbors and three Stark Law exceptions that reflect a sliding scale of regulatory flexibility for value-based arrangements. This sliding scale is based on degree of risk sharing that is incorporated into the agreement. Intuitively, the greater the amount of risk sharing incorporated into the arrangement, the more flexibility provided under the safe harbor or exception.

|

Agency |

Limited or No Risk Share |

Significant Risk Share |

Full Risk Share |

|---|---|---|---|

|

OIG/AKS Safe Harbor |

“Care Coordination Arrangements to Improve Quality, Health Outcomes, and Efficiency Safe Harbor” |

“Value-Based Arrangements with Substantial Downside Financial Risk” |

“Value-Based Arrangements With Full Financial Risk” |

|

CMS/Stark Law Exception |

“Value-Based Arrangements” |

“Value-Based Arrangements with Meaningful Downside Financial Risk to the Physician” |

“Full Financial Risk” |

A. Overview of Key Safe Harbors and Exceptions

An important initial consideration is that there are multiple differing requirements between corresponding Stark Law exceptions and AKS safe harbors. Stakeholders must navigate the requirements under both regulatory regimes for arrangements that potentially implicate each law. Although a number of commenters sought a unified set of requirements between Stark Law and AKS requirements, CMS and OIG rejected this approach, noting the different purposes of each law. In general, CMS provides more flexibility for Stark Law exceptions, given its strict liability standard. In contrast, OIG felt it was appropriate for the AKS—which is an intent-based law—to serve as “backstop” protection for arrangements that implicate both laws. The six safe harbors and exceptions set forth by OIG and CMS are as follows:

i. Limited or No Risk Share Arrangements

- The AKS Care Coordination Arrangements safe harbor protects in-kind (nonmonetary) remuneration within compliant value-based arrangements that further patient care coordination purposes. This safe harbor requires no assumption of downside risk by parties to a value-based arrangement. One example CMS uses is a skilled nursing facility providing a hospital with staff to assist in coordinating patient care through the inpatient discharge process.

- The Stark Value-Based Arrangements exception protects physician compensation arrangements that qualify as value-based arrangements, regardless of the level of risk undertaken though the arrangement.

ii. Significant Risk Share Arrangements

- The AKS Value-Based Arrangements with Substantial Downside Financial Risk safe harbor protects both monetary and in-kind remuneration and offers greater flexibility than the AKS Care Coordination Arrangements safe harbor in recognition of the assumption of an intermediate level of downside risk in a payor arrangement. As detailed below, this safe harbor requires the value-based enterprise (VBE) to take on defined percentages of downside risk.

- The Stark Meaningful Downside Risk exception is meant to protect remuneration paid under a value-based arrangement where both the physician and VBE take on downside financial risk under a payor arrangement.

iii. Full Financial Risk Share Arrangements

- The AKS Value-Based Arrangements with Full Financial Risk safe harbor is intended to protect arrangements (including in-kind and monetary remuneration) involving VBEs that have assumed “full financial risk” for a target patient population.

- The Stark Full Financial Risk Exception only applies to arrangements that involve a VBE taking on full downside risk in a value-based arrangement with an applicable payor. However, unlike the meaningful downside risk exception, it does not require a physician participating in the arrangement to also assume financial risk.

B. New Value-Based Definitions

Although the specific requirements differ as between AKS and the Stark Law, the framework is helpfully similar. CMS and OIG have largely harmonized a series of new definitions that establish this broad framework for understanding the form of arrangements that may be eligible for protection.

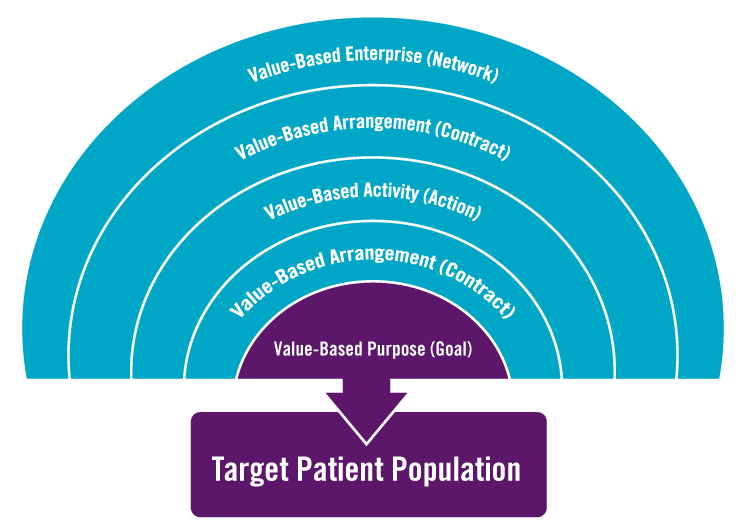

Both Final Rules are designed to only protect remuneration occurring under a “value-based arrangement” as part of a VBE. To understand what this means, a helpful place to start can be focusing on what is required to be at the heart of any permissible arrangement—the arrangement’s “value-based purpose.” Every protected arrangement must have, at its core, one or more value-based purposes, which are defined as:

(i) Coordinating and managing the care of a target patient population;

(ii) Improving the quality of care for a target patient population;

(iii) Appropriately reducing the costs to or growth in expenditures of payors without reducing the quality of care for a target patient population; or

(iv) Transitioning from health care delivery and payment mechanisms based on the volume of items and services provided to mechanisms based on the quality of care and control of costs of care for a target patient population.2

While there may be other goals to an arrangement, at least one of these enumerated value-based purposes is necessary. For example, while cost savings to a provider or maintenance of a current level of quality may very well be legitimate and valuable goals of an arrangement, such goals will not qualify as value-based purposes and will not be sufficient to obtain Stark Law and AKS protection.3

With value-based purposes in mind, the Final Rules define a “value-based activity” as one or more activities reasonably designed to achieve a value-based purpose, which can be the provision of an item or service, the taking of an action, or the refraining from taking an action.4 OIG specified that a value-based activity does not include the making of a referral.5 CMS did not make a similar exclusion6 because the definition of referral in the Stark Law already reflects a policy that referrals are not items or services for which a physician may be compensated. In other words, if the value-based purpose is the goal of an arrangement, the value-based activity is the action intended to accomplish that goal.

Value-based activities must then be set forth in a “value-based arrangement,” which is an arrangement for the provision of at least one value-based activity for a target patient population to which the only parties are: (A) the VBE and one or more of its participants, or (B) two or more participants in the same VBE.7

A VBE can be thought of as the network of participants engaging in value-based activities. A VBE might be an accountable care organization (ACO) or clinically integrated network (CIN), although a series of structures for VBEs are permissible. Specifically, a VBE means two or more participants collaborating to achieve at least one value-based purpose, where each participant is a party to a value-based arrangement with the other or at least one other participant in the VBE.8 While a VBE does not need to be a separate legal entity, a VBE must:

(i) Have an accountable body or person responsible for financial and operational oversight of the VBE; and

(ii) Have a governing document that describes the VBE and how the VBE participants intend to achieve its value-based purpose(s).

As referenced above, each value-based purpose (and thus, each value-based arrangement) must identify and be tied to a specific “target patient population.” (TPP). This TPP must be set in advance, selected using legitimate and verifiable criteria, and must further the value-based purpose of the VBE.9

.png)

C. Key Limitations to Waivers

While the Final Rules offer exciting new opportunities for providers, payors, and CINs to innovate, it is important at the onset to note several key limitations.

(i) The safe harbors and exceptions require compliance with the technical requirements for each specific type of value-based arrangements. The fact that an arrangement is associated with a legitimate value-based purpose alone will not guarantee that the arrangement will fit within one of the safe harbors or exceptions.

(ii) Much like existing AKS and Stark Law regulations, these safe harbors and exceptions are highly prescriptive, with specific requirements that are set out below. Thus, existing value-based arrangements will likely not satisfy all AKS or Stark Law value-based requirements without review and amendment.

(iii) As shown in the chart below, OIG has not limited the types of individuals and entities that may participate in a VBE. However, the AKS Final Rule prohibits certain types of organizations from relying on value-based safe harbors. These provider types are those that the OIG believe pose heightened fraud and abuse concerns. OIG revised the exclusion of these entities as VBE participants to recognize the role they may have, while denying protections for most arrangements involving these entities. While they are generally excluded from protections under the safe harbors, as discussed below, certain durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies (DMEPOS) providers and suppliers that qualify as limited technology participants may utilize the care coordination arrangements safe harbor for arrangements involving digital health technology.

|

Entity Type |

Care Coordination Arrangements |

Substantial Downside Risk |

Full Financial Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Providers and Suppliers |

Eligible |

Eligible |

Eligible |

|

Pharmacies Other Than Compounding Pharmacies |

Eligible |

Eligible |

Eligible |

|

Compounding Pharmacies |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

|

Pharmacy-Benefit Managers; Pharmaceutical Manufacturers, Distributors, Wholesalers; Laboratory Companies Physician-Owned Distributors |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

|

Manufacturer of a Device or Medical Supply (as defined in 42 C.F.R. § 1001.952(ee)(14)(iv)) |

Eligible, but only for in-kind remuneration that constitutes digital health technology |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

|

DMEPOS Suppliers (other than pharmacies or physicians, providers, or other entities that primarily furnish services) |

Eligible, but only for in-kind remuneration that constitutes digital health technology |

Ineligible |

Ineligible |

|

Health Technology Companies Not Otherwise Covered by an Entity Type on This List |

Eligible |

Eligible |

Eligible |

III. DEEP DIVE INTO EXCEPTION AND SAFE HARBOR REQUIREMENTS – LIMITED RISK SHARE ARRANGEMENTS

As part of the effort to provide protections to a continuum of arrangements, the limited risk share arrangements present the least amount of flexibility. While the relevant Stark Law exception and AKS safe harbor provide some protections, it is noteworthy that a significant number of current risk sharing arrangements in the market fall into the limited risk share category. Likewise, the Stark Final Rule includes additional and significant non-value-based changes discussed in this white paper.

A. AKS Safe Harbor – Care Coordination Arrangements

The AKS safe harbor for care coordination arrangements protects in-kind remuneration exchanged between qualifying VBE participants in a value-based arrangement connected to the coordination and management of care of the target patient population.10 Under this safe harbor, each offer of in-kind remuneration among VBE participants must be analyzed separately for compliance with the safe harbor. One key component of this safe harbor is the requirement that the recipient pay 15 percent of either: (i) the offeror’s cost, or (ii) the fair market value of the in-kind remuneration.

OIG provided certain examples of arrangements that could be structured to satisfy the care coordination safe harbor. OIG suggested that the care coordination safe harbor could be used to coordinate care between hospitals and post-acute care providers, specialists and primary care providers, or hospitals and physician practices and patients. Such coordination could involve the use of care managers, providing care or medication management, creating a patient-centered medical home, helping with effective transitions of care, sharing and using health data to improve outcomes, or sharing accountability for the care of a patient across the continuum of care. These arrangements often naturally involve referrals across provider settings, but they include beneficial activities beyond the mere referral of a patient or ordering of an item or service. The OIG stressed that it “sees a clear distinction between coordinating and managing patient care transitions for the purpose of improving the quality of care or improving efficiencies, which would fit in the definition, and churning patients through care settings to capitalize on a reimbursement scheme or otherwise generate revenue, which would not fit in the definition.”11 Likewise, the OIG noted that arrangements involving the provision of data analytics software, care managers, or remote patient monitoring could likely fit within the safe harbor. OIG specifically responded to commenters that income guarantees are not in-kind remuneration and therefore would not qualify for protection under the care coordination arrangements safe harbor.12

This safe harbor does not require parties to bear or assume downside financial risk. The OIG is concerned that the offer or provision of remuneration under value-based arrangements could present opportunities for the types of fraud and abuse traditionally seen in the fee-for-service system, particularly where the parties offering or receiving the remuneration have not assumed downside financial risk for the care of the target patient population. For this reason, and to ensure that the safe harbor arrangements operate to achieve their value-based purposes, the OIG has finalized numerous conditions and safeguards, set forth in detail in the chart below.

B. Stark Law Exception – Value-Based Arrangements

This Stark Law exception applies to physician compensation arrangements that qualify as value-based arrangements, regardless of the level of risk undertaken by the VBE or any of its VBE participants. The exception permits both monetary and nonmonetary remuneration between the parties.

CMS intends for the value-based purpose of the arrangement to relate to the VBE as a whole. The exception does not protect a “side” arrangement between two VBE participants that is unrelated to the goals and objectives (that is, the value-based purposes) of the VBE of which they are participants, even if the arrangement itself serves a value-based purpose.13

C. Takeaway – Many Major Differences Between AKS and Stark Law for Arrangements Without Downside Risk

CMS and the OIG took significantly different approaches as to no- or low-risk sharing arrangements. As a result, there is limited overlap between the requirements of the finalized AKS safe harbor and the Stark Law exception, and if a CIN or ACO wants a no- or low-risk sharing arrangement to be compliance with both the AKS safe harbor and the Stark Law exception, it will need to ensure that the arrangement meets a long list of largely non-overlapping requirements.

That said, one of the key similarities between the finalized AKS safe harbor and the Stark Law exception is the referral requirement. Specifically, both the OIG and CMS finalized requirements that the remuneration within a value-based arrangement not be conditioned on referrals of patients who are not part of the target patient population or business not covered under the value-based arrangement. This means that the value-based safe harbors and exceptions do not protect arrangements where one or both parties have made referrals—or other business—not covered by the value-based arrangement a condition of the remuneration. One example provided by CMS is that a VBE could not receive protection under a value-based Stark Law exception for a value-based arrangement between an entity and a physician that are VBE participants in the VBE if, as part of the arrangement, the entity requires the physician to refer Medicare patients who are not part of the target patient population for designated health services furnished by the entity.14 Similarly, the value-based AKS safe harbors do not provide protection for value-based arrangements that condition an offer of remuneration on: (i) referrals of patients that are not part of the value-based arrangement’s target patient population, or (ii) business not covered under the value-based arrangement.15

The following chart shows the key requirements under each arrangement:

|

AKS – Care Coordination Arrangements |

Stark Law – Value-based Arrangements |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Scope of Remuneration Protected |

In-kind remuneration only under arrangements used predominantly to engage in value-based activities that are directly connected to the coordination and management of care for the target patient population and which does not result in more than incidental benefits to persons outside of the target patient population. |

Monetary and in-kind remuneration paid under a value-based arrangement. |

|

Quality and Performance Measures |

VBE participants must establish one or more legitimate outcomes or process measures reasonably anticipated to advance coordination and management of the target patient population.

|

Outcome measures, if any, against which the recipient of remuneration will be assessed, must be objective, measurable, and selected based on clinical evidence or credible medical support. Inclusion of outcome measures in a value-based arrangement is optional. |

|

Commercially Reasonable |

Arrangement must be commercially reasonable. |

Arrangement must be commercially reasonable. |

|

Reduce to Writing |

Agreement must be set forth in contemporaneous writing signed by parties. |

Agreement must be set forth in contemporaneous writing signed by parties. |

|

Contents of Agreement |

Written agreement must include:

|

Written agreement must include:

|

|

Additional Limitations on Remuneration |

|

|

|

Referrals |

Offeror of remuneration does not take into account the volume or value of, nor condition remuneration on, referrals of patients who are not part of target patient population or for business not covered by the value-based arrangement. |

Remuneration cannot be conditioned on referrals of patients who are not part of target patient population or for business not covered by the value-based arrangement. |

|

Cost-Sharing Requirement |

Recipient pays at least 15 percent of the offeror’s cost for or the fair market value of the in-kind remuneration (either in advance for one-time costs or at regular intervals for ongoing costs). |

No similar requirement. |

|

Patient Best Interest |

Arrangement does not place any limitations on participants’ ability to make decisions in the best interest of their patients. |

No similar requirement. |

|

Directed Referrals to a Particular Provider |

Remuneration can be tied to a requirement to direct referrals to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier unless:

|

Remuneration can be conditioned on the physician’s referrals to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier when the following requirements are met:

|

|

Marketing |

Prohibits the exchange of remuneration for purposes of for patient recruitment or for marketing the items or series provided by the VBE or VBE participants. |

No similar requirement. |

|

Monitoring |

At least annually, a responsible person must assess and report on the arrangement’s coordination and management of care for the target patient population, deficiencies in delivery of quality care, and progress toward achieving evidence-based outcomes measures. |

At least annually, or at least once during the term of the arrangement if the arrangement has a duration of less than one year, the VBE or one or more of the parties monitor:

|

|

Termination |

If the VBE’s accountable body or responsible person determines that the value-based arrangement has resulted in material deficiencies in quality of care or is unlikely to further the coordination and management of care of the target patient population, the parties must, within 60 days, either terminate the arrangement or develop and implement a corrective action plan designed to remedy the deficiencies within 120 days. |

If the monitoring indicates that a value-based activity is not expected to further the value-based purpose(s) of the VBE, the parties must either terminate the agreement within 30 days or modify the agreement within 90 days to cease the ineffective value-based activity. If the monitoring indicates that an outcome measure is unattainable during the remaining term of the arrangement, the parties must terminate or replace the unattainable outcome measure within 90 consecutive calendar days after completion of the monitoring. |

|

Record Keeping |

VBE must make available all records to the secretary upon request as necessary to establish compliance. |

Records of the methodology for determining and the actual amount of remuneration paid under the value-based arrangement must be maintained for six years and available to the secretary upon request. |

IV. DEEP DIVE INTO EXCEPTION AND SAFE HARBOR REQUIREMENTS – SIGNIFICANT RISK SHARE ARRANGEMENTS

As more providers move to downside risk arrangements in the market, the protections of the significant risk share arrangement exceptions and safe harbors are likely to have the most impact on providers. Because this segment of the market has taken a significant step on the glide path to risk, the differences between the Stark Law exception and the AKS safe harbor are likely to create concern as to whether arrangements can be adequately protected.

A. AKS – Value-Based Arrangements with Substantial Downside Financial Risk

The AKS safe harbor for value-based arrangements with substantial financial risk, which protects both monetary and in-kind remuneration, offers greater flexibility than the safe harbor for care coordination arrangements in recognition of the VBE’s assumption of an intermediate level or downside risk (i.e., substantial downside financial risk). As finalized, this safe harbor applies only to the exchange of remuneration between VBEs that have assumed substantial downside financial risk and VBE participants that meaningfully share in the VBE’s downside financial risk. OIG reduced the risk sharing percentages from the proposed rule. Under the Final Rule, substantial downside risk includes shared savings with at least 30 percent loss repayment, episodic or bundled payments with at least 20 percent loss repayment, or under a partial capitation model as defined in the rule.16 This safe harbor protects remuneration exchanged between such VBEs and VBE participants if several standards are met, which are outlined in the chart below.

One key clarification in the commentary to the Final Rule is that the downside financial risk must take into account all items and services covered by the applicable payor and furnished to the target patient population, not just the items furnished by a specified VBE participant.17 As an example, OIG indicated that a VBE could not limit its risk for outpatient services by entering into value-based arrangements with a narrow set of providers that provide care in outpatient settings. OIG also clarified that the risk can be prospective or retrospective, including calculations compared to a benchmark. OIG also removed the specific 60 percent discount that was included in the proposed rule for partial capitation.

Another key distinction between this safe harbor and the care coordination safe harbor is that the VBE participant must meaningfully share in the financial risk. In the Final Rule, this requirement was set at a two-sided risk of 5 percent of the shared savings or losses of the VBE or prospective, per-patient payments for a predefined set of items and services furnished to the target patient population under the partial capitation methodology. OIG declined to finalize an exception under the corresponding CMS exception methodology under the Stark Law rules for meaningful downside risk arrangements.

In addition, this safe harbor also contains several limitations and protections found within the care coordination safe harbor, notably that the remuneration must at a minimum further the coordination and management of care for the target patient population. Other requirements include a signed agreement, limitations on directed referrals for business outside of the target patient population, record-keeping requirements, and marketing restrictions, among other requirements.

B. Stark Law – Meaningful Downside Risk Exception

The Stark Law exception for meaningful downside risk is similarly meant to protect remuneration paid under a value-based arrangement where the physician is at meaningful downside financial risk for failure to achieve the value-based purpose(s) of the VBE. Otherwise, the Stark Law’s prohibitions would not be implicated.

Although the physician must be at meaningful downside financial risk for the entire term of the value-based arrangement, the remuneration may be paid to or from the physician. Meaningful downside risk means the physician is responsible to repay or forgo no less than 10 percent of the total value of the remuneration the physician receives under the value-based arrangement. This represents a significant reduction in the 25 percent risk share required in the proposed rule.

|

AKS – Substantial Downside Risk |

Stark Law – Meaningful Downside Risk |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Risk Share Requirement |

The VBE must assume “substantial downside financial risk” from payor for target patient population within six months after entering into a value-based arrangement and the risk share must be for a period of at least one year. “Substantial downside financial risk” means, for the entire term, in the form of (each tied to historical expenditures):

The VBE participant must meaningfully share in two-sided risk based on one of the following two methodologies:

|

A physician is required to maintain “meaningful downside financial risk” for failure to achieve the value-based purpose(s) of the VBE during the entire duration of the value-based arrangement. “Meaningful downside financial risk” means that the physician is responsible to repay or forgo no less than 10 percent of the total value of the remuneration the physician receives under the value-based arrangement. |

|

Limitations on and Requirements of Remuneration |

The remuneration provided by, or shared among, the VBE and VBE participant must meet the following requirements:

|

The remuneration to or from the physician involved must meet the following requirements:

|

|

Directed Referrals to a Particular Provider |

The VBE or VBE participant offering the remuneration must not take into account the volume or value of, or condition the remuneration on:

Remuneration can be tied to a requirement to direct referrals to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier unless:

|

Remuneration can be conditioned on the physician’s referrals to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier when the following requirements are met:

|

|

Writings and Records |

In advance of, or contemporaneous with, the commencement of the value-based arrangement or any material change to the value-based arrangement, the VBE and VBE participant must set forth the terms of the value-based arrangement in a signed writing that contains the requirements listed in the Final Rule. The VBE or VBE participant must make available to the secretary, upon request, all materials and records sufficient to establish compliance. |

A description of the nature and extent of the physician’s downside financial risk must be set forth in writing. Records of the methodology for determining and the actual amount of remuneration paid under the value-based arrangement must be maintained for a period of at least six years and made available to the secretary upon request. |

|

Best Interest of Patients |

The value-based arrangement must not place any limitation on VBE participants’ ability to make decisions in the best interest of their patients. |

See limitation above regarding directed referrals. |

V. DEEP DIVE INTO EXCEPTION AND SAFE HARBOR REQUIREMENTS – FULL FINANCIAL RISK SHARE ARRANGEMENTS

CMS and the OIG have provided the most extensive protection and flexibility to the arrangement that take on full risk. However, full risk arrangements are less common in the market. While the protections offered are significant, few providers are financially able to bear full risk for a target population.

A. AKS – Value-Based Arrangements with Full Financial Risk

The AKS safe harbor for value-based arrangements with full financial risk is intended to protect certain arrangements (including in-kind and monetary remuneration) involving VBEs that have assumed “full financial risk” for a target patient population. This safe harbor includes more flexible conditions than the care coordination arrangements and substantial downside financial risk safe harbors, which the OIG believes reduces burden for the VBE and its participants. However, this safe harbor only protects arrangements between VBEs and VBE participants and not agreements among VBE participants or with downstream entities. Some of the notable requirements to meet this safe harbor are outlined in the chart below. OIG extended the phase-in period for this safe harbor from six months to one year.

Commenters asked OIG to clarify what level of stop-loss coverage a VBE could have under a full financial risk arrangement. OIG declined to do so, but it specified that it would expect stop-loss or other risk adjustment arrangements to be limited to protection for the VBE against catastrophic losses and not as a means to shift material financial risk back to the payor or another third party–i.e., the VBE must maintain material financial risk.18

OIG recognized that this safe harbor would apply to a limited number of providers, but it promulgated the safe harbor to remove a potential barrier to providers taking on additional risk.19 OIG did note that some state laws limit the ability of providers to take full financial risk without forming licensed health plans or meeting other licensure requirements, and OIG indicated providers must still comply with state law.

B. Stark Law – Full Financial Risk Exception

The Stark Law exception for full financial risk applies to value-based arrangements between VBE participants in a VBE that has assumed “full financial risk” for the cost of all patient care items and services covered by the applicable payor for each patient in the target patient population for a specified period of time. Like OIG, CMS increased the time period before the VBE must be a full financial risk to one year from six months as originally set forth in the proposed rule.

Like OIG, CMS addressed questions regarding stop-loss by not limiting an amount of loss mitigation but indicating that such mitigation should not shift material financial risk to the payor.20

CMS explains that this exception requires that the VBE is financially responsible (or is contractually obligated to be financially responsible within the six months following the commencement date of the value-based arrangement) on a prospective basis for the cost of all patient care items and services covered by the applicable payor for each patient in the target patient population for a specified period of time.

|

AKS – Full Financial Risk |

Stark Law — Full Financial Risk |

|

|---|---|---|

|

VBE Risk Share Requirement |

The VBE must assume full financial risk (or is contractually obligated to be at full financial risk within the one year following the commencement of the value-based arrangement) from payor with signed writing evidencing full risk for a minimum of one year. “Full financial risk” means the VBE assumes financially responsibility, on a prospective basis, for cost of all items and services covered by the applicable payor for each patient in the target patient population. |

The VBE must assume full financial risk (or is contractually obligated to be at full financial risk within the 12 months following the commencement of the value-based arrangement) during the entire duration of the value-based arrangement. “Full financial risk” means that the VBE is financially responsible on a prospective basis for the cost of all patient care items and services covered by the applicable payor for each patient in the target patient population for a specified period of time. |

|

Limitations on Remuneration |

The remuneration exchanged between the VBE and a VBE participant must meet the following requirements:

|

The remuneration exchanged must meet the following requirements:

|

|

Directed Referrals to a Particular Provider |

The VBE or VBE participant must not take into account the volume or value of, or condition the remuneration on:

|

Remuneration can be conditioned on the physician’s referrals to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier when the following requirements are met:

|

|

Writing and Record Requirements |

The value-based arrangement must be set out in a writing signed by the parties that specifies the material terms of the value-based arrangement, including the value-based activities to be undertaken by the parties, and is for a period of at least one year. For a period of at least six years, the VBE or VBE participant makes available to the secretary, upon request, all materials and records sufficient to establish compliance. |

Records of the methodology for determining and the actual amount of remuneration paid under the value-based arrangement must be maintained for a period of at least six years and made available to the secretary upon request. |

|

Quality Assurance Program |

The VBE must provide or arrange for a quality assurance program that protects against underutilization and assesses the quality of care furnished to the target patient population. |

No similar requirements. |

VI. ADDITIONAL VALUE-BASED SAFE HARBORS AND EXCEPTIONS

A. AKS – Safe Harbor for Arrangements for Patient Engagement and Support to Improve Quality, Health Outcomes, and Efficiency

A common component of value-based arrangements is the desire to provide in-kind assistance to patients to help ensure adherence to a treatment plan, with a goal of improving health outcomes and reducing overall costs. In addition to potential AKS barriers, such assistance can also be problematic under the beneficiary inducements CMP law, which penalizes remuneration to a beneficiary when the offeror knows or should know the remuneration is likely to influence the selection of a provider.

Accordingly, this AKS safe harbor will allow VBE participants to offer patients in the VBE’s target patient population with beneficial tools and supports to improve quality, health outcomes, and efficiency by promoting patient engagement with their care and adherence to care protocols. Notable requirements to meet this safe harbor include the following:

(i) Goods, items, and services given to target patient populations as patient engagement tools or supports are provided directly to patients by VBE participants (or their agents);

(ii) The patient engagement tool or support must not be funded or contributed by a VBE participant that is not a party to the applicable value-based arrangement, or by the list of enumerated entities that cannot rely on the value-based AKS safe harbors as set forth in Section II.C (e.g., pharmaceutical companies);

(iv) For a period of at least 6 years, the VBE participant makes available to the Secretary, upon request, all materials and records sufficient to establish compliance;

(v) The availability of a tool or support is not determined in a manner that takes into account the type of insurance coverage of the patient.

(vi) The aggregate retail value of patient engagement tools and supports furnished to a patient by a VBE participant on an annual basis cannot exceed US$500 unless such patient engagement tools and supports are furnished to patients based on a good-faith, individualized determination of the patient’s financial need; and

(vii) The patient engagement tool or support meets the following requirements:

- It is in-kind and is (i) preventative, (ii) health-related technology/monitoring, or (iii) designed to identify/address social determinants of health.

- It has direct connection to coordination and management of care for the population.

- It does not include any cash or cash equivalent.

- It is not used for patient recruitment or marketing.

- Does not result in medically unnecessary or inappropriate items or services reimbursed in whole or in part by a Federal health care program.

- It is recommended by the patient’s licensed health care professional and advances one or more of the following goals:

- Adherence to treatment regimen;

- Adherence to drug regimen;

- Adherence to follow-up care plan;

- Prevention or management of a disease or condition; or

- Ensuring patient safety.

B. Stark Law – Exceptions Applicable to Indirect Compensation Arrangements

Under the longstanding Stark Law regulations, if an indirect compensation arrangement exists, the exception for indirect compensation arrangements at 42 C.F.R. § 411.357(p) is available to protect the compensation arrangement. The indirect compensation exception includes requirements not otherwise found in the exceptions for value-based arrangements. Thus, this creates the possibility that when a value-based arrangement exists in the chain of financial relationships, the indirect compensation exception may technically not be available to protect the relationship.

Accordingly, CMS finalized in the Stark Final Rule an amendment to the indirect compensation exception to address this issue.

Under the revised exception, parties will determine whether the indirect compensation arrangement to which the physician is a direct party qualifies as a value-based arrangement eligible for a Stark Law exception.21 If so, the exceptions for value-based arrangements will be applicable under the indirect compensation exception.22

C. AKS – Other Safe Harbors

The AKS Final Rule also includes other new safe harbors and changes to existing safe harbors that are not specifically related to value-based care. These changes include: a new safe harbor for CMS-sponsored model arrangements, a new safe harbor for donations of cybersecurity technology, a new safe harbor to codify statutory changes made to the definition of remuneration for Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs operating a CMS-approved beneficiary incentive program, and revisions to existing safe harbors for personal services arrangements, warranties, local transportation, and electronic health records. Addressed in a separate white paper, the AKS Final Rule includes other new safe harbors and changes to existing safe harbors, including several not specifically related to value-based care. Detailed information on these significant changes to the AKS can be found here.***

VII. CONCLUSION

For years, many stakeholders have noted that the Stark Law and AKS rules were not designed for value-based arrangements, which often necessarily impact referral patterns as a method of improving quality and reducing costs. Notwithstanding the complexity and number of requirements created by the Final Rules, these value-based safe harbors and exceptions ultimately represent a major regulatory shift that recognizes the reduced need for aspects of these laws that were designed in part to prevent overutilization. CMS’s and OIG’s rule each recognize the lessened need for some of the regulations when providers are bearing financial risk and therefore have a financial disincentive for increasing utilization. The new rules will offer providers, payors, and other stakeholders the opportunity to unlock a wide range of new innovative arrangements with greater flexibility under the fraud and abuse laws. In the short term, hospitals, physicians, and post-acute providers will have new opportunities to coordinate and provide in-kind assistance to further care coordination purposes. Longer-term, greater opportunities may be present for CINs and ACOs when downstream participants and physicians in a CIN are ready and willing to share in downside risk within payor arrangements, which will unlock a much broader scope of possible protection.

Providers and CINs will need to comprehensively assess the practical compliance elements of the Final Rules. In particular, given the scope of proscriptive requirements, it is unlikely existing arrangements qualify under any of the new proposals without at least some level of amendment. K&L Gates’ health care practice can assist health care providers in conducting this analysis and will continue to closely monitor issues related to the AKS and the Stark Law, particularly in the value-based context. Accordingly, we will provide updates regarding new developments, as well as the industry’s response to these new regulatory flexibilities.

K&L Gates’ multidisciplinary team of lawyers is positioned to advise stakeholders on a broad spectrum of health care, life sciences, and technology matters, including Medicare program integrity initiatives, and to facilitate stakeholder engagement with CMS through the development and submission of public comments.